Vol. 2, Issue 77 - September / October 2018

Posted: Sunday 16th September 2018

2018 seems to be flying past at a speed I would like to be able to match on the bike. We haven’t attended as many rides away from home as we usually do for various reasons and the fact that on some weekends there are up to three or four events we would like to attend on the same day. We made our annual pilgrimage to the Bodensee in Bavaria for two weeks of very enjoyable cycling, partly due to sunshine every day bar one (when we managed to visit a gallery in Lindau hosting an August Macke exhibition) and in no small way due to the billiard table smooth roads wherever we cycled. Cycling in the UK these days consists of constantly dodging potholes and riding on uneven surfaces and we are always being told we have the fifth largest economy in the world!

For many years we have yearned to do a couple of trips on bikes using river towpaths, one from Passau to Vienna on the Danube and the other in Southern France using the Canal du Midi and I feel we must do at least one next year so we are busy researching and trying to find a hire firm doing really small bikes for Patricia. One problem is that although the frames are smaller (on the hybrid bikes they use) the bars on their raised stems remain at the same height and I can imaging the bars being level with Patricia’s face. I think this is influenced by the design of Dutch bikes which have become very popular here, especially amongst girls and young women. The problem comes about because the frame head tubes remain the same length in order to keep some distance between the top and bottom bearings which reduces the stress on them. It seems that all models of this type of bike have a ‘riser’ adjustable stem but the irony is that in lowering the stem this takes the bars further away making the reach impossible.

The logistics of taking your own bikes are quite complex. We may be able to overcome this hire bike problem on the Danube as we have seen one machine for hire which may fit the bill but there seems to be no flexibility in machine type on the Canal du Midi.

We have received no material for this edition of Lightweight News so I am carrying on with reproducing interesting items from the website which you may have missed.

Spares for Cinelli (and other Italian bikes) the website http://cyclomondo.net/page9.htm

Has some useful replacement bolts, etc for Cinelli if you are in need of some for a restoration. These bolts are notorious for breaking or going missing and are hard to find. They also have some parts for other Italian classics as well as a selection of decals for each.

Restoring Pedals

Author Peter Brown

In response to an enquiry from me, Peter describes the painstaking way that he restores pedals – when they are done they look as good as new. Whether all platers would be as cooperative I don’t know. See image above for the finished article – Editor

Here is the procedure I use for re-chroming pedals. As you see, they are plated complete but after being dismantled for cleaning and polishing:

Pedals are firstly dismantled in the normal way and then degreased using Carplan Tetroclean. Next they are derusted using Rustins Rust Remover. The threads and bearing surfaces are cleaned out with a wire brush on a Dremel: this is important as platers tend to polish threads clean and you can lose thread if you don’t do it yourself. The next part is to dismantle the cage, which is the only way that they can be repolished inside and out.

I use a Dremel SpeedClic cut-off disc, as flat as possible to the plate, and remove just enough of the burr to be able to prise the plates apart, for which I use a modified auto disc brake pad separator. Once they are separated I check that they are the correct shape and then remove about 3 file strokes from each shoulder of the tenons in order to replace the metal lost in separation.

Everything then goes into an ultrasonic cleaner to make sure they are as clean as I can possibly get them before the plates and barrels then go off to the platers for them to polish. When they come back it is easy to think that they have already been plated, so good is their polishing.

The assembly needs to be done quite quickly and the assembled cages returned to the platers before any tarnishing occurs. First of all, check that you have all the plates the correct way round and make sure all the tenons are seated tightly in the mortices. The next part is very important, and that is to clamp the end plates into the barrel ends, and then tape the pedals tightly together with insulating tape, just leaving the tenons protruding through the side plates. This prevents the end plates spreading as the tenons are riveted over. You need a solid lump of metal to work on, and then use the small end of a ball pein hammer to re-rivet them. Once you are sure they are solid they go back to the platers for plating, along with the spindles and any other parts, asking them to give them a final clean and polish before doing so. Once they come back again they can be completely assembled with new bearings.

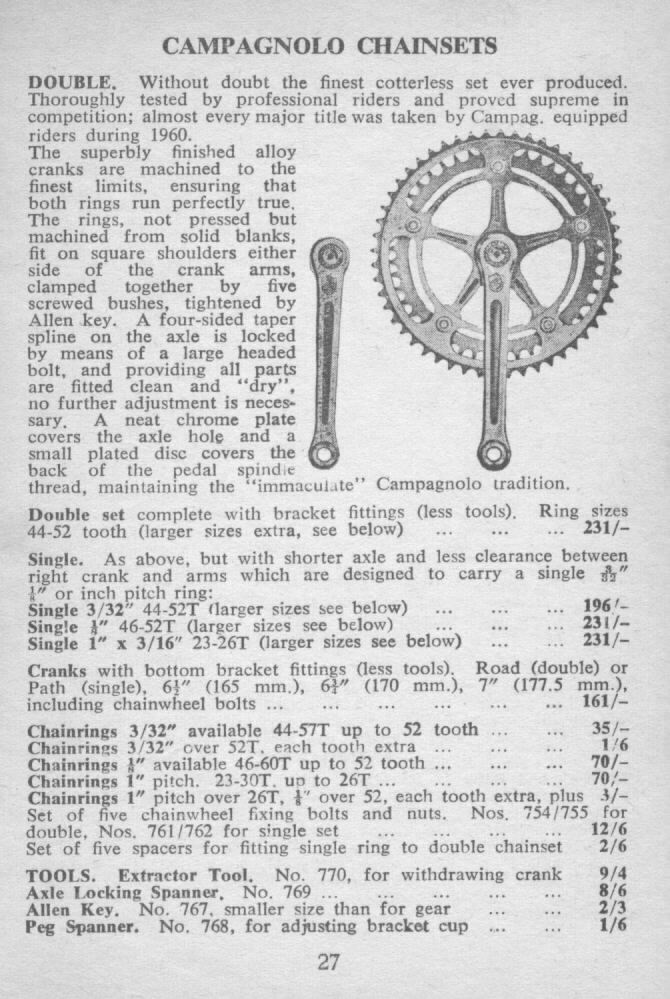

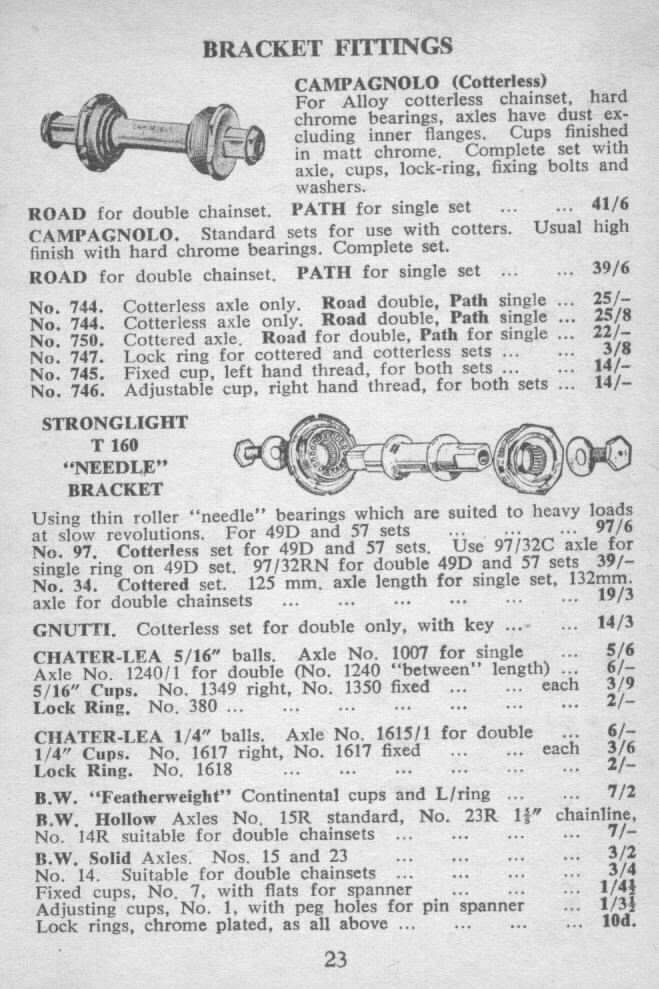

Chainsets and bottom brackets from Aids to happy cycling 1961 – a useful guide to restoration:

Edoardo Bianchi – the early years Author: David Carpenter

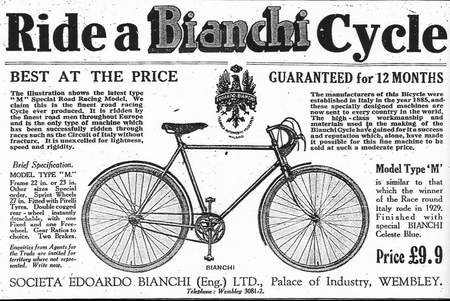

Edoardo Bianchi – a brief history of the famous Italian manufacturer of cycles, motor-cycles and cars. (Information from Edoardo Bianchi by Antonio Gentile:

The Bianchi story begins on the 17th July 1865 when Edoardo Bianchi was born in the shadow of Milan’s famous Duomo. He was taken into care at the local Martinitte orphanage. For Edoardo the orphanage was to prove a formative and indispensable experience. By the tender age of seven years, along with a basic education, he had also received the first rudiments of mechanical instruction that were to prove so important to his future career. New social and economic changes induced by the phenomenon of industrialisation were taking place.

The young Edoardo was sent into the world as a mechanic’s apprentice. Right from the start he set aside part of his earnings in order to make regular donations to the institution that had raised him as a child. Early on he was already displaying the charismatic force which would lead him to the forefront of Italy’s expanding industrial system.

Edoardo opened his first workshop at No’ 7 Via Nirone in 1885. Right at the outset he vowed to achieve his personal and professional independence by adopting a frank and honest approach to his business dealings; above all his policy was to offer a high-quality finished product using only the best materials. Choosing at the outset to diversify his production, the workshop could supply velocipedes, invalid carriages, precision instruments, electric doorbells (!), surgical instruments, and wheel hubs.

But Edoardo’s imagination was immediately drawn to the construction of bicycles. Early designs were soon discarded when Edoardo produced a model with equal sized wheels, a feature soon copied by the many competitors across Lombardy. And so the Italian bicycle was born. Improvements to the original soon followed. In 1888 the expanding Bianchi firm moved to Via Bertani. Also in that year, Edoardo applied John Boyd Dunlop’s idea to fit an air-filled rubber tyre. Five years later a new factory was open in Via Borghetto. Around this time Edoardo was summoned to the royal court to teach Queen Margherita the art of cycling. Lessons were given in the park of the royal villa at Monza using a special “Bianchi” featuring a crystal chainguard. Other titled ladies followed: the Duchesses of Aosta and Genova, Queen of Napoli and Princess of Portugal. King Umberto decided in 1895 to appoint Bianchi as official suppliers by Appointment to the Royal Court. This distinction entitled Bianchi to make use of the coat of arms of the royal house of Savoy. More awards followed at the trade fairs at Rome, Bologna and Milan and the Exposition International du Salon de Cycles in Paris. Cycling had arrived!

The newly-founded Italian Touring Club organised trips out into the countryside and the new sport of cycle racing soon followed. Bianchi naturally soon made a name for itself. All the same, Edoardo would never turn his back on the bicycle in spite of developing motorised versions which ultimately became motor cycles and automobiles.

Giovanni Tommaselli caught Bianchi’s eye in 1897 when he won the Italian championship riding a Prinetti e Stucchi on the track at Alessandria. Tommaselli was immediatedly hired and competed in the 1899 Paris Grand Prix. Edoardo, who was a good scout, hit the bullseye here too.

In what was considered the World Championship of track racing Tommaselli won the admiration of the Parisian public as he held off an extremely strong field to win. The Italian cyclist’s French success was to have an extremely positive effect across the board. Apart from bringing Bianchi international prestige Tommaselli’s feat sent the sales curve shooting upwards. He later became one of the firm’s top financial managers.

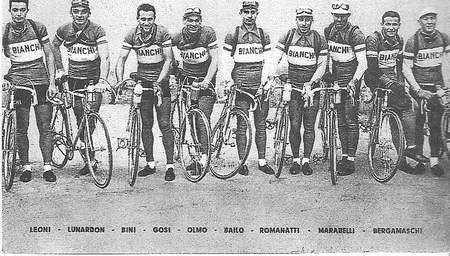

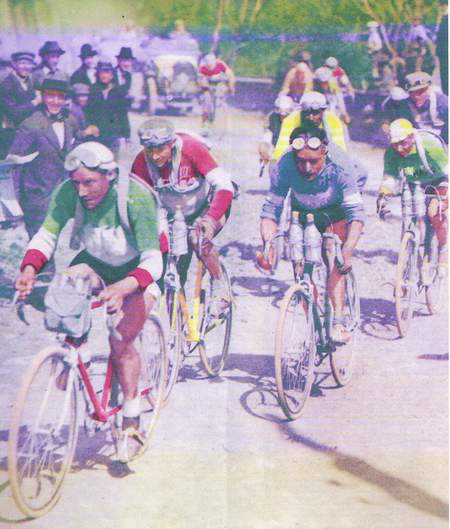

The cycling team went from strength to strength in their sky-blue and white colours, winning the Giro d’Italia, Italian Championship, Rome-Naples-Rome, etc. These early riders included Galetti, Oriani, Pavesi, Azzini, Sivocce, Cervi, Agostini and Bruschera, all under manager Erminio Cavedini. Other great wins included Rossignoli, who in June 1906 covered the 181 kms from Milano to Torino in 4 hrs 47′ 22″.

Gerbi won the 340 km National Endurance Race on 23rd July 1905, and Cuniolo covered 176 kms in 6 hrs 35′ 34″ to win the King’s Cup on 1st Oct 1905. The faithful team manager played major roles in the company for over 50 years. The motor racing team was also very successful. One of the drivers was Alfieri Maserati, later to build his own racing cars.

In 1912 the bicycle catalogue contained 14 different models – for “ladies, children, priests and gentlemen”. Prices were from 185 lire to 460 lire. By the end of 1907 a new factory was needed to cope with the car production. This was built at 16 Viale Abruzzi in Milan. It was to be the head office for many years to come.

By 1922 the bicycle list included two Giro d’Italia models. Wins in the prestigious Milano-San Remo came to 16 in the first 50 years. Belloni won the Giro de Lombardia for Bianchi in both 1915 and 1916. Later on, the first of the great, Constante Giradengo (see Milano-San Remo image above) joined the team. He was to become the first Campionissimo and with Pavesi they were to have a great influence on Fausto Coppi’s career. The Bianchi that Petit-Breton rode to win the first Milano-San Remo race in 1907 is displayed in the Museum of Science and Technology in Milan together with Fausto Coppi’s 1947 machine, both frame finished in the famous celeste colour.

In 1922 bikes were equipped with Coventry chains and Bowden Touriste brakes. The racing tem was doing well. Seres won the Paris 6-day; Giradengo was successful in the Giro di Romagna and Giro dell’Emilia. Belloni won stages in the Giro and Gremo the Giro di Piemonte. During this time the motor cycle team was equally successful with the star rider, Tazio Nuvolari. Again, the machines were finished in the celeste colour and the riders wore sky blue and white jerseys.

By 1932 cycle production was up to 70,000 units per year and great importance was placed on the promotional value of the Bianchi team performances. In 1939 the team was looking very professional with 9 riders led by Giuseppe Olmo, who had set a new hour record in 1936 of 45.090 km. Alberto Ascari joined the motor cycle team. He was later to become Formula One champion in 1952. The bicycles available in 1939 were the Scelta Corsa, which had wooden rims and tubulars. The Folgore model had the Campagnolo 3/4 speed Corsa gear … The rest is history!

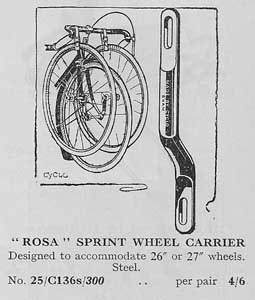

Sprint-wheel carriers by Peter Underwood

Many cyclists in the 40’s and 50’s had only one machine. It would often be an immaculately kept top-of-the-range machine but it had to serve all purposes. Some owners even used this machine to commute to the factory or other place of work. There was a fair chance that it would be equipped with a low-geared fixed-wheel, especially in the winter. It could be that the owner would ride to work on his bike during the day and train in the evenings – probably with winter wheels and mudguards.

Come the weekend our rider may be entered in a time-trial, perhaps 15 – 20 miles away, which would possibly entail setting off from home at 4.30 – 5 am remembering that most events started at 6 am. For this event he would fit his shiny, expensive racing sprints with light silk-walled tubs to his front axle using sprint wheel carriers as the rider on the right has done. The carriers were angled forward to give clearance for the feet on the pedals. The tops of the wheels would be fastened to the drops (bars) with toestraps to stop them vibrating over the bumps and possibly slipping down.

At the race the guards, and lights if they were needed, would come off and the sprints (with higher gear of course) fitted. The roadsides around the start would be a mass of clothing, mudguards and wheels – all left quite happily and never stolen.

After the race, which could well be over by 8am, the machine would be rebuilt with lights, mudguards and training wheels and the club members would ride to the nearest cafe for breakfast before setting off on a club run of probably 100 miles plus completed with the sprints still attached. If you look closely at photographs of runs taken post-WWII you may spot a member so equipped.

On some hub axles there was little or no thread to spare when the wheel was in the forks and the track (or wing) nuts were tightened. This meant that when the carriers were put on behind the nut, the wheel was only secured by a few threads. One way round this with track nuts was to put them on back to front thus obviating the loss of threads caused by the washer. A slight setback is that one needed an open-ended spanner to do this, a ring or box spanner wouldn’t work on the nut. Peter Brown has sent us an image of a rare component designed to solve this problem – a pair of front axle extenders, shown here.

Neil Manning on working for T J Quick

I started working with Tom in ’87 straight out of school. Someone left so I jumped at the chance and asked if he needed help.

Everything about T J Quiock on your site sounds about right but I can add a few details.

From what Tom told me he used to race with Ron Cooper and Ron used to come round regularly to use the shot blast machine we had.

He also built cars in his time before moving to the Stanstead Road site. I remember about him working for Holdsworths. We made the Allez branded pannier racks for them even when I was there.

We did trade work for the Holdsworth shop and Roy Thame making new frames under their brand names. He also did work for other local shops, resprays and repairs.

Behind the shop was a workshop, but out of the rear of the building was a paint shed and a large workshop where we did metalwork. He employed a few people at some point, but when I was there it was just 3 of us. We made all of the shoe racks for K-Shoes shops plus other assorted jobs like chimney breast supports, gas fire bases which had to be custom made and even high-end light fittings for offices up in the city. It all supplemented the income as the shop was pretty quiet during the week.

We took orders on Saturdays and then worked on new frames and repairs/resprays during the week.

Tom was/is a genius with making things. We did everything including tandems, trikes, lo-profile, BMX, he even invented his own bike that split in half to fit in the boot of a car. As a keen golfer he created his own electric golf trolley which we made for a while. If he couldn’t find a part he would just make it. I remember the local chrome platers ruined a pair of American classic car bumpers so we filled in the holes with plates and got them back to how they should look. It was such an interesting time with so many varied jobs.

Tom is still doing well at 88 years old and still making things in the garage.

This information has been added to the T J Quick page under Classic Builders on the website.

FOR SALE by Chris Hutchinson

H. R. Morris Road/path, exactly as shown on the Classic Lightweights site https://www.classiclightweights.co.uk/bikes/hrmorris-rb.html’, £650.

Chris Hutchinson, Billericay.

FRAMES FOR SALE Bryan Clarke

22” Shop built Holdsworth Professional frame, 1972, TJQ, refurbished, one off build, £175

22” George Brooks frame 1956, Nervex pro lugs, refurbished, believed built by Ephgrave, £200

23” Curly Hetchins Experto Crede frame 1952, good head badge but poor paint, £420

22 ½” Hinds frame Lewisham c 1967, refurbished £175

23” HEG Ferris Super Champion frame, c 1950, refurbished, Lytaloy headset £200

Also, bikes for Sale

1947 Stephens Special, 23” frame, Williams, Chater pedals, Burlites, S/A FM and LF Airlite on Dunlop LAs, oval badge B17, Reynolds girder stem and bars, Bluemels guards. £500

C1946 Evelyn Hamilton,22 ½” frame, 3 speed Osgear, Stronglight/Durax, BOA pedals, oval badge B17, Hiduminiums, FBs on Fiamme, GB spearpoint and Maes bars. £650

Posted: Sunday 16th September 2018

This article appears in the following categories.

Upcoming Events

Whether you are looking for a gentle social meet up, or a 100-mile ride browse the community’s upcoming events and plan your next weekend outing.