Vol. 2, Issue 74 - March / April 2018

Posted: Friday 16th March 2018

March is here and we have uploaded details of many rides for 2018 under Ride Calendar on the website. We have several from both Yorkshire and Durham this year so no excuses if you live ‘North of Watford’.

Bob Johnson’s Cicli Artigianali have helped Rapha create a fantastic display of Colnagos at their Rapha Shop in Brewer Street, London W1 so if you are the Big Wicked City make sure you drop by and see these pearls from the CCI members. They will be on display until mid-April.

If you have a liking for Italian Classics we have an interesting collection of information on the website at: https://www.classiclightweights.co.uk/italian-classics.html

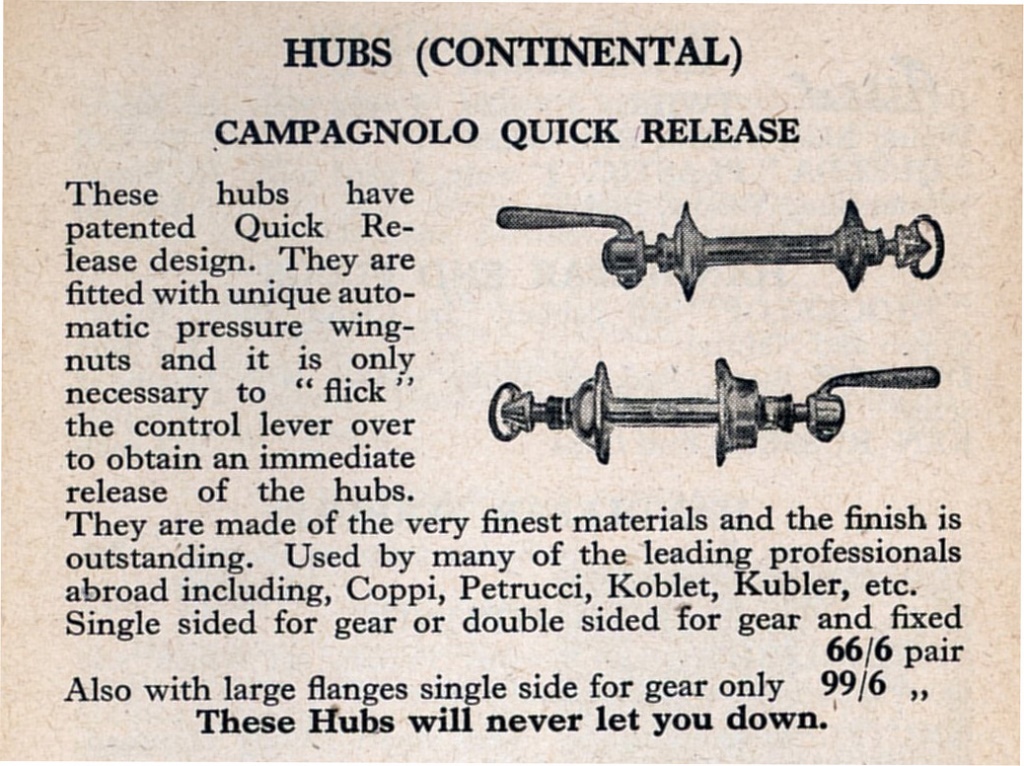

Here I have included a few snippets from Holdsworth’s Aids to Happy Cycling – 1954. They show a selection of the components available that year and supply basic technical information in some cases.

Chater-Lea produced two bottom bracket sets, one with ¼” balls and a larger one often used for tandems with 5/16” balls.

1954 is the first year Holdsworth advertised the Campagnolo Q R hub so it could also be the first time they were sold in the UK

I was delighted to read the article by Geoff Orange about Jack Hearne.

I was an 11-year old cycling fan who in 1961 dreamt of one day moving to France or Belgium to become a professional cyclist.

Living in Langley Jacks shop in Slough, near the Railway station, it was my local serious bike shop and had the benefit of being on my daily ride to school.

As the youngest member of Maidenhead cycling club in 1961 I was a frequent fixture in his shop and he very kindly allowed me to pay for items using the famous Club card as my pocket money permitted.

Using my nickname ‘Bun’ one day he said that I might as well work in the shop, which I happily did for several years at weekends and during school holidays, cleaning bikes and brewing the copious amounts of tea that were consumed each day in the shop.

In the 60s his frame building skills were amongst the best and as well as being a continual source of encouragement he built me a frame to suit my modest size.

Finished in bright orange with black Hearne transfers it was a de rigueur frame of the time in double butted Reynolds 531 with Campag fork ends and slightly sloping fork crown plus some nice lugwork.

Over time I was able to top the bike off with Campag Record, Mavic rims and Mafac centre pull brakes plus the obligatory Brooks professional saddle … well softened and shaped!!

My family moved away to the West country in the mid-1960s and although I kept in contact with Jack for several years afterwards eventually we lost contact.

My love of bikes and cycling fostered by Jack has continued to this day and I am sure he would have a wry smile and no doubt one of his appropriate expletives that at the age of 52 I rode my first of 3 Etape du Tours plus all the major Italian Grand Cycle Sportifs and yes I finally did make the move to France at the age of 63! where I ride my bike with friends from the local club several days each week.

Jack was a great frame builder, bike mechanic and friend.

Unfortunately, whether using brazed on or clip on Campagnolo lever bosses, the centre bolt works loose very easily, unlike, for example, the Simplex lever, which has a very substantial centre bolt wing nut. Discard the slotted Campag centre bolt and substitute the little Campag wingnut with the wire thumb grip. Under the wingnut place a spring washer, or better still a serrated washer, which sits against the chrome washer atop the base of the lever. The gear lever will not now slip, particularly when out of the saddle, but the wing nut will allow small adjustments while riding.

If using Campag handlebar levers, you will find that the extra length of the lever and body will cause you to bang your knee on the lever when climbing out of the saddle, this can cause the gear to change up when you least need it. To compensate and take the levers further away saw approx. one inch (in old money!) off the end of the bars, and angle the straight part of the bars downwards and slightly away from the rider.

If, like me, you like very tight cable adjustment which is quite difficult with handlebar levers, fit a pair of cable adjusters (the excellent Suntour if you can get) with barrel adjusters into the lever bosses on the down tube. If you have standard Campag downtube handlebar double cable stops of the clip-on type, discard these and use the lever bosses on a clip-on Campag down tube lever, minus the levers! Hope this makes sense.

ED.: I have had this problem with the slotted screw head for ages and try to carry a small stubby screwdriver to tighten up when it slips, always at an in-opportune moment. Usually grabbing that lowest gear for a steep stretch of road only for the gear to slip back into a higher gear! I think I have a spare ‘wing’ nut so will use this piece as a spur to get the job done instead of thinking about it. The pros used the Simplex Retro-friction lever as soon as it came out much to the annoyance of their sponsors.)

As we have not received much copy for this edition I have copied another piece from ‘Reminiscences’ – this time on time trialling. Apologies if you have already read and digested this:

Time Trials in the 1940’s/1950’s

Or – The Men in Black

Peter Underwood

In the last few years of the nineteenth century the racing of bicycles on public roads was banned, due in no small part to the lobbying of horse riders and pedestrians. Races were being wilfully disrupted, often by the police themselves, and this resulted in the National Cyclists’ Union banning racing on public roads for fear of all cycling being banned.

Independent-minded cyclists decided to organise events themselves designed to conceal the fact that they were actually racing from the general public. Thus was spawned the ubiquitous time trial where cyclists individually ride a prescribed out-and-back route timed by an official timekeeper.

It was decided that events should start at the crack of dawn and all participants must dress in black from head to toe in order for them to be less conspicuous! This way the racing was often all done and dusted by about 8am. They also decided to designate all the courses by a secret coding and to this day races are held on, for example, the ‘E10-25’. If I told you where that was then they would have to kill me! This coding system was devised to prevent any publicity for the event, possibly attracting spectators and creating the atmosphere of a race proper. Some years (1952) later Eileen Sheridan had a successful Land’s End-to-London record disallowed because a newspaper casually mentioned that it was being attempted and some club folk turned out to support her.

I started time trialling just after world war two and the racing was still done dressed in black from head to toe, at the crack of dawn and on courses designated by numbers – the start sheets were declared to be secret and confidential although I must admit you weren’t compelled to eat them after reading! Pre-war it had been compulsory to wear a black alpaca jacket when competing but this was dropped for post-war racing, possibly as a recognition of the fact that clothing was only available in exchange for ration tickets.

The format of a time trial was as follows: First, the event must be organised and approved by the governing body which results in the event being listed in the RTTC Handbook, the time triallists bible (now the CTT Handbook).

On the day the organisers have to arrange for a pusher-off who holds the cyclist with both feet strapped in the pedals on the start line (probably a painted or chalked line about one inch wide from the kerb out into the road for about two to three feet). Standing next to the line is the timekeeper (with an assistant for bigger events) with his stopwatch who sends the riders off at one-minute intervals; he gives a five-four-three-two-one count down at which time the pusher-off releases the rider – years ago they gave quite a push!

The club has to provide marshalls at any junction deemed to need one for safety and to stop the rider going off course. In the 40’s/50’s the ‘turn’ consisted of a turn marshall standing in the middle of the road and the rider had to spin round in the road behind him. He also shouted out his number to the turn marshall who noted all the riders’ numbers down for the timekeeper.

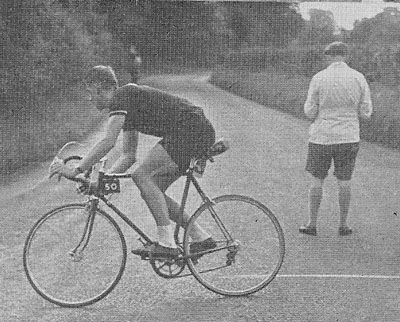

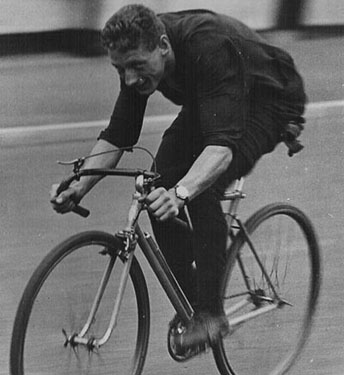

The rider then sets off as fast as he can to the finish where the timekeeper will have crossed the road to a white line on the other side. Here he positions himself to click the stopwatch as the rider speeds by, again shouting out his number. There are sometimes handicaps organised within the event as well as age-related adjustments. Quite often photographs taken in this era were of the rider manoeuvreing around the turn, although this is not always obvious. The giveaway is the bike leaning over at about 15 – 25º and often the inside knee stuck out.

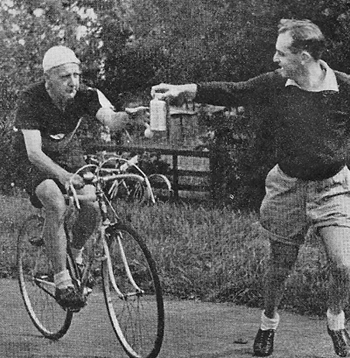

For events over fifty miles the organising club provides a feeding station where club members hand up drinks, food, and sometimes wet sponges to the passing riders. For longer rides competitors from the larger clubs would have their own feeding teams in addition to those provided by the organisers. These took care of special diets, etc. and the feeders would also check other riders’ times in order to give their man information on his performance in relation to his competitors.

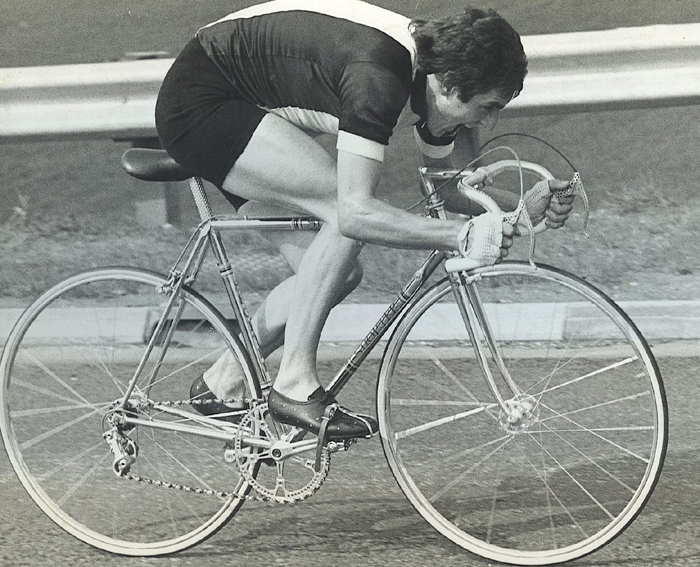

Early post-war virtually every competitor was riding fixed-wheel for these events. In the winter riders used gears of about 64″ for training and often the first events of the season were restricted to 72″. As the season progressed riders raised the gears to about 84″ for the shorter events and 81″ for the longer 100-mile, 12 and 24-hour events.

Looking back from our relatively affluent living style it is hard to imagine the living conditions for the years in question. Just about everything was rationed and though the war was over, ration allowances were being cut even from the levels during the time of hostilities. Materials, such as steel, were in short supply and most of what was available was earmarked for export. Adverts for cycle components often stated that there was a short supply due to most production being exported.

Bearing this in mind it is surprising that such beautiful frames with elaborate lugwork and finishes were produced and even more amazing that they sold in such numbers. People were often living up to ten in a small house, which could well have no bathroom and an outside toilet. On Fridays the tin bath would be taken down from its hook on the wall and the whole family would take it in turns to have their weekly scrub; the last one in probably came out dirtier than when they went in!

Most riders had just the one machine which acted as transport to work, and was used for weekend clubruns, touring, and racing on the road and track. The mudguards were on and off like. (insert your own simile here!) and the best wheels would be used for racing only with an inferior pair for general use. At factory gates, hundreds, and in some cases, thousands of workers on bikes would pour out at knocking-off time, not all clubmen of course.

Women were not allowed to compete in the same races as men so clubs had to organise separate events for them. A few clubs were formed for women only, such as the Rosslyn Ladies CC, and they organised some of the larger events.

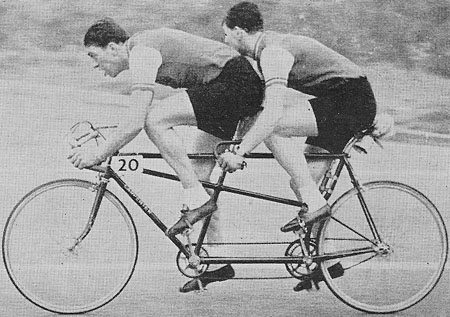

Events were also organised for tandems. Solo trikes would compete in normal time trials for solo machines. There may be a prize for trikes (or barrows as they were known) but barrow-boys tended to pit themselves against each other in a sort of limited fraternity. Tandem trikes would compete in tandem events of course.

In 1960 the ‘Uni’ 30-mile tandem event attracted 65 entries, small fry though compared with the same event in 1936 which had 135 entries for an event limited to 100 riders.

One final aspect of the time trial scene is the end of season hill climb when all the seven stone riders came into their own. Early events were ridden mainly on single-speed track frames – some with brakes, some without.

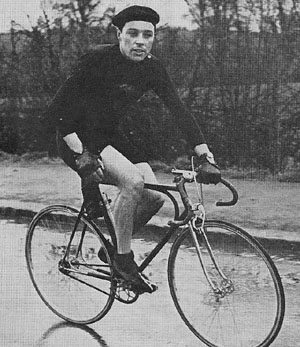

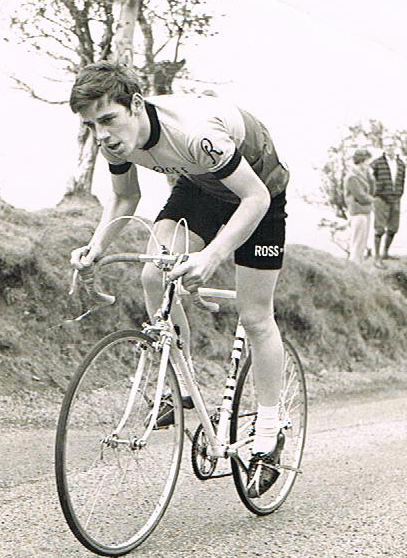

Below is an image of Terry Harradine taken when several riders opted for gears. Having said that, the hill climb season still sees its fair share of single-speed machines.

“I have just read your article on time trials with the pictures of Basil Francis and Ruth Smith.

I was out on a ride with a couple of friends on the Birmingham to Evesham road when we caught up with Basil who was riding in company with a lady. We rode and chatted as a group for a while when Basil said to his companion something like “see you at the usual place” and then set off at a serious pace. The lady explained that it was his usual practice, in the course of a gentle potter, to have a serious “dig” at a certain point and then wait for her to catch up. We rode on for a while until she said to me “why don`t you go after him, he would enjoy a chase”. Basil was out of sight by this time but I decided to have a go and set off, leaving my two friends to ride with the lady. Needless to say I did not catch him but found him waiting by the side of the road outside a barbers shop in Evesham where I waited with him till the group caught up. We then went our separate ways.

The picture of Ruth Smith was of interest to me because of the cars in the background, a TC M.G and a Lancia Lambda. I purchased this Lambda UU 1738, a 1929 8th series car with a shortened wheelbase and one of only two, I understand, with twin carburettor cylinder heads, in 1959 from a dealer on Coventry Road, Birmingham. I had part exchanged a Morgan three-wheeler for the Lambda and was horrified to discover that the Lancia only gave about 16 miles to the gallon as compared with 40 for the Morgan. I did enjoy the Lancia and did many miles in it but the fuel costs were too much of a drain on my pocket so I went back to the dealer and did another part exchange this time for a 1928 Brough Superior J.A.P S.S.100 with alloy launch sidecar.”

The Tour Classic is part of the Tour of Cambridgeshire Festival and is the UK’s ONLY closed-road cycling event which is dedicated to riders who love to ride a true-classic on vintage road bikes.

Tour Classic is held on fully-closed roads and gives riders the opportunity to, not only polish their Pre-1987 classic to showcase, but also to race against others and compete for the Tour Classic podium positions. If you don’t fancy the hustle and bustle of the race then come and ride your beautiful masterpiece, enjoy the English weather with the pan-flat 56-mile route and rub shoulders with other vintage lovers.

Dress to impress with your traditional clobber, be part of the Concours d’Elegance and show-off your classic bike, as well as get cheered on by thousands of spectators around the traffic-free route. With a lunchtime-start, you can enjoy the morning having a wander through the Cambridgeshire Bike Show, where you’ll find a dedicated Classic and Vintage section, as well as join us for a bacon bap and cup of tea before passing the TC start line.

The criteria for the Tour Classic are:

- Vintage steel-framed road racing bicycles built before 1987 or Vintage style road race bikes.

- More recent ‘retro’ steel frames may be eligible, provided they are of ‘classic’ design and fitted with pre-1987 equipment or similar replica parts.

- The only aluminium bikes permitted are ALAN and VITUS style frames of the correct period, having either screwed or glued lugs.

- Only friction, ’non-indexed’ gears may be used, with either down tube levers or pre-1980 bar-end shifters.

- Pedals should ideally be of period design, ideally with toe clips and straps.

- Gear and brake cables may run within the frame but must run outside of both the handlebars and the handlebar tape.

- Both tubular tyres and clinchers with tubes are permitted.

- Riders are allowed wider gear ratios than those originally fitted.

- Cyclists who have a disability and would like exemptions to these criteria should contact the organisers in advance.

As the Tour Classic is a race, riders are required to wear cycling helmets manufactured to current recognised safety standards.

ERRATUM: THE CLASSIC CYCLIST’S 2018 NEW YEAR QUIZ

In the original, Q.5 read:

Who won the first post-WWII Tour de France in 1948?

a) Hugo Koblet b) Jean Robic c) Roger Walkowiak

This should have read:

Who won the first post-WWII Tour de France in 1947?

A: b) Jean Robic

Posted: Friday 16th March 2018

This article appears in the following categories.

Upcoming Events

Whether you are looking for a gentle social meet up, or a 100-mile ride browse the community’s upcoming events and plan your next weekend outing.