The Outdoor Cycle tracks of 20th Century Durban, South Africa

Posted: Sunday 23rd August 2020

‘A bicycle track or velodrome is an oval riding surface made of wood, cement or macadam, the better ones being either cement or wood. Wood seems to be the fastest surface and cement is reasonably fast, but macadam or blacktop is not that responsive. There are basically two different shapes of tracks. There is the more oval–shaped or egg–shaped track and then there is the cigar–shaped or long type with short bends the egg–shaped, more oval track has a nice flow when you’re riding it, but the cigar–shaped can be a little abrupt going into the turns and coming out. The reason for the banking is for safety, to keep you from slipping when you go around the turn. On really good tracks usually the banking is not symmetrical. The banking going into the turn is a little less steep than the banking coming out of the turn. When you come out of the turn onto the straightaway it goes downhill a little bit to the next turn and so forth. The bike flows around again. There are several different lines running around the track surface. The inside one is called the pole line and is where the track is measured. The sprinters’ line runs parallel to and 70 centimetres to the outside of the pole line. The line halfway up the track is called the stayers’ line and was put there for motor pacing. It can also be used as a guide for team racing.’ Jack Simes. Winning Bicycle Racing (1976:109–114).

Durban’s Olympic Velodrome of the 1980s

In the South African east coast city of Durban in 1980, a new municipal outdoor cycle racing track was under construction. It was much publicised locally as being the nation’s first ‘state of the art’ 333 metres per lap Olympic standard velodrome. But this was at a time when South Africa’s competitive cyclists were internationally isolated. Since the 1960s South Africa had been excluded from the Olympic Games because of the apartheid policy of racial discrimination in sport. The nation’s cyclists had also been barred from competing at the annual UCI world championships since 1970 (2). Moreover, this sporting isolation was to continue until the end of apartheid in the early 1990s.

The then new egg–shaped Durban track was constructed using pre–cast reinforced pink coloured cement panels supported on buttresses, with maximum bankings of 40 degrees. A sizeable covered grandstand overlooked the home straight. The new venue was scheduled to be shared with local equestrians who would use the grassed infield for horse shows, gaining access to this via a tunnel under one of the track’s bankings. It was anticipated that the new facility would be a hive of sporting activity throughout the year and regularly attract considerable numbers of spectators to slickly–run cycle race meetings and horse shows.

However, even before the new stadium was completed, a bitter behind–the–scenes dispute arose within the local cycling fraternity over the naming of the new facility. One faction was in favour of it being named in honour of a leading local cycling personality; a second faction was totally opposed to any such move.(3) The person in question was Cyril Geoghegan, who had been a leading local racing cyclist in the 1930s. He had subsequently become a top cycling official, organiser and administrator, culminating in his being elected national president of the South African Cycling Federation (SACF) for ten successive years during the 1960s. Moreover, he had been largely instrumental in negotiating for the building of the new cycling stadium with Durban’s municipal officials.

A forceful and outspoken personality, Geoghegan was a controversial figure in the sport, attracting both loyal followers and vehement critics amongst the local cycling fraternity. Amongst the allegations levelled against him by his detractors was that it was during his tenure as SACF president that South African cycling was suspended sine die by the UCI and furthermore that he had not even bothered to attend the 1970 UCI Congress at which this decision was reached.(4) Nevertheless, in 1981 his supporters finally succeeded in persuading Durban’s municipal authorities to agree to the new cycling track being officially named the ‘Cyril Geoghegan Cycling Stadium’ in his honour. Nicknamed ‘Go’ Geoghegan for his energy, his pre–war speciality had been motor–paced track racing which he had also practiced on a visit to Australia. Local legend has it that he obtained the plans for the new Durban track from a cycling contact over there and that somewhere in Australia there is an identical velodrome.

At a gathering of local cyclists immediately prior to the opening of the new venue, Geoghegan’s address was listened to politely if somewhat sceptically. With visionary zeal he maintained that the stadium would be used for the staging of six–day races. He also insisted that, because of the new track’s steep bankings, it would be necessary for them to revert to using old–fashioned shellac in order to securely glue on their tubulars. However, the six–day races never subsequently materialised and modern synthetic tubular adhesives proved perfectly adequate to the task and easier to use.

In 1981, Cyril Geoghegan was fêted at the official opening by Durban’s mayor of the new stadium bearing his name. He passed away in the mid–1980s.

But the Cyril Geoghegan Stadium of the 1980s was by no means either the first or the only cycle racing track to exist in Durban during the 20th century. Rather, from the late 19th century onwards the city’s cyclists had enjoyed the use of a succession of such facilities.

Albert Park: Durban’s First Cycle Track

The visitor to Albert Park today would find it almost impossible to believe that this is the site of Durban’s original cycle track. This is because, during the current post–apartheid era, all traces of it have disappeared and the park itself has become a haven for many refugees from other African countries who live rough in its unkempt grounds. The park and its immediately surrounding area form part of what is now central Durban. Topographically it is a flat, low–lying area adjacent to Durban’s bay, which is a natural harbour that first attracted British settlers to the region in the early 1800s.

During the late 19th century, however, the Albert Park locale originally developed as a residential neighbourhood of imposing colonial bungalows inhabited exclusively by the town’s white elite. The park itself – named after Queen Victoria’s consort – provided the white populace (it was reserved for exclusive use by ‘Europeans only’, as signs at park gates stated) with a superb recreational facility. It incorporated a grandstand overlooking an expansive oval sports field for cricket and football matches and this was surrounded by a grass athletics track. This in turn was encircled by a long flat oval cycle track of compacted gravel which was used in late Victorian and Edwardian times for both leisure cycling and cycle racing. Cycling had become a highly fashionable activity in Britain at the time and it spread rapidly throughout the British Empire and particularly to colonial cities like Durban which has a subtropical climate of mild winters and warm, humid summers,

Details of early competitive track cycling in Durban remain elusive. However, according to the official South African Cycling Federation’s history (Jowett, 1982):

- In 1899, ‘South African’ track cycling championships (which were purportedly first held in Port Elizabeth in 1882), were staged in Durban and presumably in Albert Park. (5)

- In 1900, the British Crown Colony of Natal in which Durban and the capital Pietermaritzburg were the main centres, boasted a total of three cycling clubs: Durban CC, Maritzburg CC and Speedwell CC (also in Pietermaritzburg).

- In 1905, the ‘South African Amateur Athletic and Cycling Association’ (SAAA&CA) was formed and thereafter organised joint athletics and cycling championships on an annual basis in different centres.

- These SAAA&CA championships were held in Durban in 1907 and again in 1911 with the Albert Park track presumably being the venue on both occasions.

- From the1907 Durban event onwards, the SAAA&CA championship track cycling titles contested at these meetings consisted of the quarter mile, the half mile, the one mile, the 10 mile and the 25 mile–motor paced events.

- Annual Natal colonial athletics and track cycling championships had first been instituted in 1904 under the auspices of the ‘Natal Amateur Athletic and Cycling Association’ (NAA&CA) which was formed in that year.

- This Natal body subsequently affiliated to the SAAA&CA and, in addition to the national championship distances, the Natal championship title events included the ¾ mile. The Albert Park track was again presumably the Durban venue for these contests.

However, the advent of the First World War saw the suspension of competitive cycling throughout South Africa between1915 and 1919. The first phase in competitive track cycling in both Durban and South Africa thus came to a close.

The Interwar Years: Lords Ground Athletics and Cycling Stadium at the Old Fort

In the two decades between the two World Wars, the joint national athletics and cycling body (SAAA&CA) in association with its provincial affiliates like the Natal AA&CA did much to promote these sporting codes amongst the white population. During this period, exclusively white South African national teams of cyclists and athletes began to participate in both the Olympic Games and the British Empire Games on a regular basis and this served to further stimulate local competition and public interest. Throughout, the governing bodies and local clubs continued to host regular joint athletics and cycling meetings.

In Durban in the early 1920s a dedicated new athletics and cycling stadium was built by the municipality in an area near to the historic Old Fort (which the British forces had defended against the Boers in skirmishes during the early 1800s). This new venue was known as ‘Lords Ground’ and it was to continue to be used by both athletes and cyclists for some thirty years until the mid–1950s. It incorporated a 440 yards long, eight lane hardened cinder athletics track surrounded by a 460 yards per lap tarmac cycle track with 20 degree bankings.(6) There was a wood and iron grandstand on the main straight and the track was bordered by a picket fence, allowing spectators to find vantage points around the stadium which they did in large numbers on race days.

The exact provenance of Lords Ground is unclear. According to one local source (Jackson, 2003: 46–7):

‘The Natal Cricket Union was established in 1890 and Durban’s first proper cricket ground was the Lords ground which adjoined the railway property in Old Fort Road. The railways later needed the site for their own purposes and so, in 1922, the Kingsmead (cricket) ground was established at its current location’.

The same source notes in its chronology of the year 1912 that:

‘The Natal Motorcycle Club is formed and holds its first meeting at the Lords Ground in Old Fort Road on 20 January’. (Jackson, 2003: 27). Elsewhere it is reported that, also in 1912, Mahatma Gandhi held a meeting with dissident local Indian indentured labourers at Lords Ground. Another report alludes to the Comrades Marathon (a long–distance annual road running race between Pietermaritzburg and Durban, established in 1921 and still held today) as finishing on the athletics track at Lords Ground in 1923. This suggests that the venue was already serving as an athletics and cycling stadium by this date.

Around this time also, the Albion Harriers, which had previously been a purely athletics club extended membership to cyclists and became the ‘Albion Harriers Athletics and Cycling Club’. It came to include Cyril Geoghegan in the ranks of its leading members.

The South African national athletics and cycling championships were held under the aegis of the SAAA&CA at Lords Ground in 1924, 1927, 1932 and 1940. Throughout this interwar period the main track cycling championship titles remained the ¼ mile (440 yards), the ½ mile (880 yards), one mile, five mile and 10 mile events. However, the 25 mile–motor paced event was dropped in the late 1930s while the 1 000 metres individual time trial was introduced along with the match sprint event and the 4 000 metres team pursuit at that time.

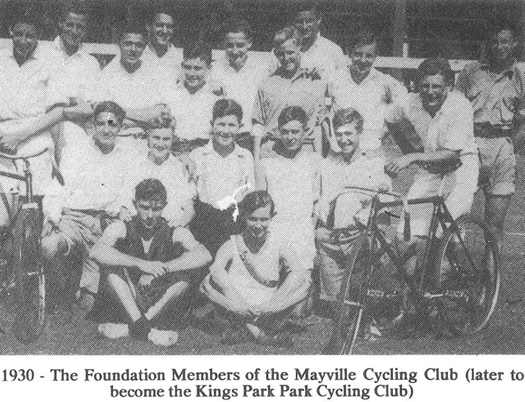

That Albert Park had been replaced by Lords Ground as Durban’s main track cycle racing venue is attested to by an account in a history of the Mayville Cycling Club, which was formed in Durban in 1930, to the effect that:

‘the (new) club decided to hold some track meetings but, as they were not then affiliated to the Natal Amateur Athletic and Cycling Association, they were debarred from using the track at the Old Fort Sports Grounds. This did not dampen the enthusiasm of the club and they promptly held their events on the flat running track in the old Albert Park Grounds. These events proved popular and more and more riders joined the club. In November 1930 the Mayville CC was accepted as an affiliated club by the NAA&CA and from there the club grew from strength to strength…

James Cyril “Go” Geoghegan was a member of Albion Harriers and Cycling Club but he resigned from there in 1932 to join the Mayville CC’ (Huckett n.d.: 1).

The major attraction of the Mayville CC was that it was a club dedicated exclusively to cycling although its members continued to participate in joint athletics and cycling track meetings.

With the advent of the Second World War, however, competitive cycling was again discontinued throughout South Africa until hostilities ceased in 1945.

The post–World War II era: Cycling in Durban enters the Age of Apartheid

The ending of World War II was followed by a rapid revival of sporting activities, including cycling, in South Africa and in this regard the situation in Durban was no exception. Lords Ground track remained the epicentre of local ‘whites only’ cycle sport. This was despite its surface having deteriorated badly making it extremely bumpy, while its facilities including the grandstand had suffered through neglect during the war years when it was requisitioned by the military. Local cyclists in the post war era also had difficulty in obtaining quality racing machines, equipment and tyres all of which, being imported, were both expensive and in short supply. According to ‘Faggi’ Thompson, sprints and tubulars were reserved exclusively for track use and the many riders who commuted to and from the track relied on wheels shod with 26” Endrick HP rims and Dunlop Sprite tyres, using sprint carriers to transport their track racing wheels. The poor state of the Lords track together with the equipment problems, with old and patched racing tubulars often being used, probably contributed to the numerous serious racing accidents which occurred at this time.

However, according to the Mayville CC history:

‘In 1948 Cyril Geoghegan organised the Durban Grand Prix (match sprint event)…and brought out a British team. British sprint champion Alan Bannister was the first winner. At that meeting 106 riders competed for prizes totalling ₤150. This meeting really got the public interested in cycling and lots of youngsters were attracted to the sport as a result.’ (Huckett, n.d.: 5)

The six–man British track team consisted of Lew Pond (captain), Alan Bannister, Dave Ricketts, Tommy Godwin, Ron Meadwell and Ian Scott (7). They beat a Natal provincial track team in a series of races at Lords ground and then toured the country. In the only ‘test match’ contested against a South African team held in Kimberley the British team won by 33 points to 6 (Jowett, 1982: 60).

The immediate post war period was thus a time when exclusively white competitive track cycling boomed in South Africa and both Durban clubs and riders were in the forefront. Following on tandem match sprinting being introduced as a national and provincial title event in 1949, the Mayville CC imported two Hobbs of Barbican track racing tandems. In both 1950 and 1951 the Mayville pairing of Johnny Ramsay and Rudi Vorster won the national tandem title. Various overseas track teams and riders were also brought out during the early 1950s, including the 1948 Olympic sprint champion Mario Ghella and the American trackman Jackie Heid, whose visit to South Africa was sponsored by the Mayville CC of which Cyril Geoghegan was by then the dynamic president. (8)

However, in 1954 Durban’s ageing Lords Ground track was demolished and a new purpose–built velodrome was promised to the local white cycling fraternity by the Durban municipality. Around this time also, white athletes and cyclists at both the national and provincial levels decided to go their separate ways organisationally and in 1957 the independent South African Cycling Federation (SACF) was established along with provincial bodies like the Natal Cycling Union (NCU). This initiative saw the disbanding of the once–powerful Albion Harriers AA&CC in Durban leaving the Mayville CC as the city’s sole white cycling club.

Thus far this account has been exclusively preoccupied with track racing amongst Durban’s white cycling fraternity. However, Durban has been a multicultural place ever since its establishment in the early 1800s. In 1948, the city’s population totalled some 332 000 inhabitants of whom only 35% were whites (or ‘Europeans’, as they were then generally called) while 65% were people from African, Indian and Coloured backgrounds (9). In terms of formal general sporting facilities let alone cycling tracks, nothing had been made available to Durban’s people of colour who had historically (i.e. always) been barred from using those available to whites. Only during the 1920s was a tract of land known as ‘Currie’s Fountain’ set aside for use as a sporting facility initially for local Indian people. It subsequently became the multi–sports centre for all of Durban’s ‘non–white’ residents.(10)

It was in demand throughout the year, being used primarily for football (‘soccer’, in local parlance), cricket and, to a lesser extent, athletics. While its exact provenance remains unclear, at some stage a flat cinder surfaced cycling track was laid around the perimeter of Currie’s Fountain. It was there that, during the 1950s, members of the Avondale Cycling Club, formed amongst Coloured and Indian youths who lived in the vicinity, trained and raced. This club and its members not only existed entirely independently of local ‘whites only’ cycling, they were totally ignored by it. However, the Currie’s Fountain cycle track was destined to deteriorate largely as a result of the heavy usage of the venue by other sporting codes and the crowds these drew. By the time of the establishment of the Bayview Wheelers club in the late 1950s, again with both Coloured and Indian members drawn from the neighbourhood, it was to all intents and purposes unusable.

But the year 1948 saw the election of a new white national government which, through its institution of the policy of ‘apartheid’ or total racial segregation, was to set South African society on a fateful course. Apartheid was to impact on all spheres of life including sporting activities. In Durban, as elsewhere, large scale removals and relocations of people of colour occurred.

In the late 1940s, a large hostel complex for African men, most of whom were migrant workers from rural areas, was constructed on the southern fringes of the city in an area known colloquially in isiZulu as ‘Wema’. Officially called the ‘S.J. Smith Hostel’, it was designed to house more than 4 000 men in dormitory accommodation. In the early 1950s the S.J. Smith (Wema) Stadium was added as a sports facility for the hostel complex. This consisted of a football pitch and a banked tarmac cycling track of some 500 metres in length together with a grandstand. The Wema stadium was reserved for the exclusive use of Africans and the provision of such ‘separate amenities’ was entirely in keeping with the apartheid state’s segregationist policies.

This segregation extended into the organisation of sport itself. While the details are sketchy, according to one source in 1949 an organisation calling itself the ‘South African Amateur Athletics & Cycling Association (Non–European)’ was established. According to this same source, it was under the auspices of this SAAA&CA (Non–European) that ‘The first South African cycling championships for non–whites’ were held in Durban in 1957, (presumably) at the Wema stadium.(11)

Details of these championships are lacking but the indications are that the competitors, who were all Africans, were drawn from South Africa’s gold mines and from the state–owned South African Railways and Harbours (SAR&H) which had an associated sporting division. In Durban at that time, the small pool of African racing cyclists were primarily SAR&H employees belonging to its sporting association which subsidised them to a certain extent. (African riders were mounted on old, second–hand track machines with Claud Butlers being the most common).

However, members of Durban’s Coloured cycling community, faced with the demise of the cycle track at Currie’s Fountain, also began to surreptitiously use the Wema track for training purposes. But much as had been the case at Currie’s Fountain, the Wema stadium was in great demand for football matches and practices. As a result, the pursuit of track cycling at the venue became increasingly fraught with difficulties.

The era of the Kings Park Athletics and Cycling Stadium

When the Lords Ground track was demolished in September 1954, the Durban municipality had promised local white athletes and cyclists that they would soon have a new state–of–the–art stadium. As matters transpired, however, it proved to be a three year interval during which time locals were obliged to travel to Pietermaritzburg to race on the Sax Young track which had been constructed in 1937 and is still in use there today. At 503 yards per lap and with 15 degree bankings, its setting in Alexandra Park is a highly attractive one.

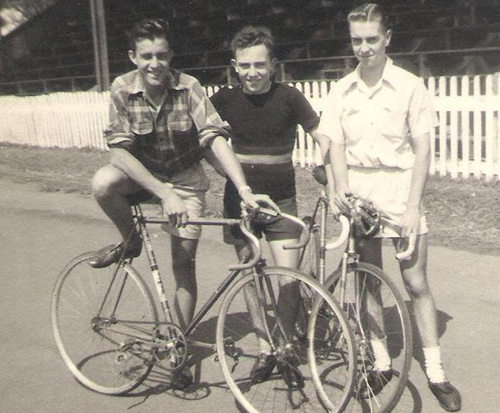

In 1958, however, Durban’s new athletics and cycling stadium was unveiled in the Kings Park sporting precinct to the north of the CBD and city’s beachfront. This incorporated a 400 metres long, eight lane cinder surfaced athletics track and a 460 metre lap cycling track. The track was surfaced with pink cement and had maximum bankings of 33 degrees. Riders immediately declared it ideal, its smooth surface allowing them to use light tubulars, with Dunlop No.2s being great favourites before the advent of Italian Cléments and Pirellis in the 1960s. On the new track, Italian built Frejus track bikes with their close clearances and chunky stays and the similar Legnano framesets rapidly found favour amongst top local riders and soon superseded the longer wheelbases and pencil–stays of British ‘path’ frames by the likes of Hobbs of Barbican which were prone to whip on the fast, steep bankings. Carlton ‘Flyers’ were also popular along with some Claud Butlers. Locally made DHC and Jowett framesets began to feature increasingly as leading riders appeared on them. Cinelli track machines and a few Dutch RIHs appeared on the local scene later.

The SACF national track championships were held at the Kings Park stadium first in 1958 and then subsequently in 1968 and 1975. Such was the stimulus of the new venue that a new cycling club, the Durban CC, was established at this time and affiliated to the NCU. (Jowett notes the existence of a ‘Durban Cycling Club’ in 1900 but there is no subsequent record of it). Ultimately, the new stadium was to figure in the Mayville CC’s decision to change its name after 31 years. The new name adopted was the ‘Kings Park Cycling Club’ which it has retained through to the present day. As a club history explains this decision:

‘In 1961 the club changed its name to Kings Park Cycling Club, a decision that resulted only after much discussion and a determined push by (the)…then chairman. Although membership was open to all and was very cosmopolitan, Mayville was a “coloured” area of Durban and it was thought that “King’s Park” was a more racially neutral name as well as indicating the address of the club headquarters’ (Huckett n.d.: 7).

At least three notable changes in the racing occurred at the new Kings Park track. The first was the introduction of a ‘Junior’ (U19) category in the 1950s and then, in the late 1960s, of a ‘Juvenile’ (U14) category. These were also introduced into both the provincial and national track championships in a move to recruit more young riders. The second change was a steady movement away from events based on the standard Imperial mile (¼, ½, ¾, 1, 5, and 10 miles) and towards those based on metric measurements (1 500m, 1 000mTT, I 000m match sprint, 2 000m tandem match sprint, 5 Km., 10 Km., and 20 Km.). The third change, in concert with these others, was a movement away from handicap events which had been the norm when there was only ‘open’ racing involving riders of all ages and towards ‘scratch’ or ‘bunch’ racing amongst seniors, juniors and juveniles respectively. (12)

These changes resulted in track meetings in Durban (and nationwide) becoming increasingly characterised by bunch races of longer duration, events for different age categories being duplicated and the chances of upset results with newcomers or riders of modest ability winning (always a strong possibility in handicap races) drastically reduced. Coincidental with these changes was a steep decline in spectator attendance at track meetings, suggesting a causal link between this and the racing changes.

But while provincial and national track championships did continue to attract a measure of public attention, weekly Friday night track racing meetings under floodlights involving riders from both Durban and Pietermaritzburg formed the staple diet of summer track seasons at Kings Park stadium. These ran from each September through to Easter of the following year attended by only a handful of spectators.

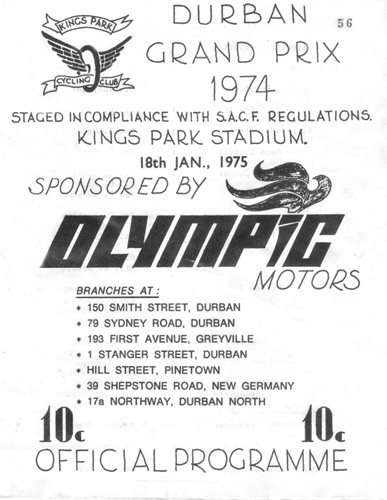

The big exception was Kings Park CC’s ‘Durban Grand Prix’ meeting, first staged in 1948 and traditionally held in January. While this event had disappeared from the racing calendar in the late 1950s, it was revived in 1972 and continued on an annual basis thereafter. It regularly drew large crowds. The Durban Grand Prix centred on a blue riband 1 000 metres match sprint event which regularly attracted the current cream of South Africa’s track sprinters who provided quality racing. Supporting this was an Omnium based on points and composed of a series of bunch events (typically 1 500m, ten lap ‘point–to–point’ and 10 Km.). For instance, in the 1974 edition, a total of 51 riders participated in the meeting. In the match sprint final, Pietermaritzburg’s Ralph Smout (the 1973 national sprint champion) beat Joe Billet from Kimberley (who had been the national sprint champion in 1970 and 1971) to the title of Durban Grand Prix Champion.

The ACUNA era at Kings Park Stadium

‘History was made at King’s Park Stadium on Saturday when Coloured cyclists held their first club meeting.’

Daily News (Tuesday, January 28, 1975). This small news item in a Durban newspaper pointed to two new developments: firstly, to changes in the apartheid state’s sports policy in an effort to overcome international sporting isolation; and secondly, to the flourishing of competitive cycling amongst Durban’s Coloured community which had occurred entirely independently of the white cycling fraternity.

Previously, the apartheid state had designated all sporting facilities for the exclusive use of specific racial groups and the Kings Park Stadium had been restricted to use by whites since its inception 18 years earlier in 1957.(14) In 1974, however, the apartheid state declared certain sports venues racially ‘open’ facilities and the Kings Park Stadium was one of these.

As I have detailed elsewhere (Cycle Sport in Apartheid’s Shadow), starting in the 1950s, competitive cycling took root in Durban’s Coloured community and expanded rapidly during the subsequent decades under the influence of the ‘Amateur Cycling Union of Natal’(ACUNA) and its national body, the ‘South African Cycling Association’ (SACA). With the demise of the cycling track at Durban’s Currie’s Fountain, however, local Coloured cyclists were left without access to any track facilities. Some did succeed in making surreptitious use of the Wema track but ACUNA was prohibited by law from organising race meetings there since it was a facility designated for use exclusively by African cyclists. In the wake of the changes made by the apartheid state, however, for the first time ever ACUNA was able to apply for its members to utilise the Kings Park track for both training and racing. The event reported on in the Daily News item was therefore a major milestone in the history of local track cycling as it was the first track meeting that ACUNA officially organised in Durban.

When, later in 1975, the SACF held its national track championships at the Kings Park track, a total of 219 riders entered for the event. However, the entrants did not include a single cyclist of colour. This was because, while the apartheid state had indeed made certain concessions, these did not extend to allowing open competition between cyclists from different racial backgrounds. Instead in terms of the new policy, people could only compete against others of the same racial background at club, provincial and national levels. Thus the 1975 SACF event in Durban remained, as previously, essentially the ‘white national track championships’.

ACUNA and its affiliated clubs were subsequently to organise numerous track meetings at the Kings Park stadium including the SACA national track championships there in 1976.

In 1976, however, rumours first began to circulate that the Kings Park Stadium was scheduled to be remodelled. Athletes were dissatisfied with the cinder based athletics track which had been superseded by newer all weather ‘tartan’ tracks elsewhere. It was mooted that a new cycling track also be built in Durban.

On the organisational front, the sporting ‘concessions’ made previously by the apartheid state failed to have the desired effect of South Africa regaining admission to international competition. As a result, further concessions were made. In cycling, the SACF and its provincial affiliates like the NCU became involved in making overtures to SACA and ACUNA. The promise was that if these latter bodies agreed to merge with the former then there would be no racial discrimination at club, provincial and national levels. It is not clear what occurred in these negotiations other than that they took place in great secrecy. Suspicions remain about the role of the apartheid state and its agencies in the negotiations. In the end, in the late 1970s SACA merged with the SACF and ACUNA with the NCU. In Durban the ACUNA clubs rapidly disappeared and those of their members who continued racing became members of Kings Park CC.

Finally, in July 1979 the cycling track at Kings Park was demolished, having been in existence for 22 years. Work subsequently started on what became the Cyril Geoghegan cycling stadium where the first track racing meeting was held on 20th December, 1981. But in the 1980s also, a new stadium incorporating a football field and banked cycling track was built in the African township of Umlazi to the south–west of the Wema stadium area. It was there during the 1980s that Durban’s existing cycling clubs – Kings Park CC and Triangle CC – staged a series of weekly track meetings in an initiative aimed at recruiting Africans into the sport with limited success.

Durban’s Cycle Racing Tracks in the 21st Century

In an interview with Cycling Weekly the designer and builder of London’s 2012 Olympic velodrome, the Australian Ron Webb who has been responsible for many cutting edge velodromes in recent times, is reported as saying: ‘If we look at (track) racing, it’s a facilities–led sport now and for the countries that don’t have the facilities for training, it’s difficult. The chances of seeing someone coming from Africa or even America where they don’t have those sorts of facilities are very low.

It’s making it more elitist and that’s not a good idea with the Olympics. It does’nt fit with the Olympic ideal – but I think that is long gone.’

State–of–the–art velodromes in the 21st century are invariably indoor arenas, short (333 metres or less) and are wood surfaced. Ron Webb’s temporary indoor tracks range from 146 metres to 160 metres per lap in length while his permanent velodromes (like Manchester in the north of England) are 250 metres long. Durban’s two remaining tracks are situated outdoors, cement surfaced and only one is 333 metres long. Both the Umlazi track and the Geoghegan stadium have been in existence for some 30 years.

In the circumstances, if Ron Webb’s observations are correct then the desire for Olympic track cycling successes that motivated Durban cycling personalities like Cyril Geoghegan in the past are likely to remain a chimera. However, in the wake of the 2010 FIFA World Cup, there has been talk of Durban bidding for a future Olympics. Perhaps, therefore, the dream of a truly modern Olympic velodrome for Durban is not totally ‘pie in the sky’.

- This article is based on a combination of personal experiences, oral histories gathered from leading local cycling personalities of various ages and backgrounds and from both printed and internet sources. I am particularly indebted to Garth ‘Faggi’ Thompson and Archie Barnwell for their unflagging interest and support. Ultimately, however, I am solely responsible for the article’s flaws.

- ‘In 1963 South Africa was suspended by the International Olympic Council in terms of the Olympic Charter. (Rule 1 forbids any discrimination on the grounds of race, politics or religion and Rule 24 emphasises the ability of National Olympic Committees to be able to resist political or such other pressures as might prevent them from adhering to Olympic principles). In 1970 at the UCI Congress in Leicester, England, South Africa was suspended by the Union Cycliste Internationale…’ W. Jowett. 1982. Centenary: 100 Years of Organised South African Cycle Racing. South Africa: South African Cycling Federation. (pp.12–13).

- Durban’s cycling hierarchy strongly supported the idea. However, influential figures in the Natal Cycling Union (NCU) with strong ties to cycling in the provincial capital of Pietermaritzburg and who also held high offices in the South African Cycling Federation (SACF) were totally opposed. At an NCU committee meeting I attended at which the matter was heatedly discussed, one Pietermaritzburg delegate declared: ‘I am totally opposed to anything being named after any living person’.

- In a 1976 interview with the British cycling journalist John Burns, the incumbent SACF president, Raoul de Villiers, who had served as Cyril Geoghegan’s vice–president for several years, dismissively remarked: ‘I don’t remember his Christian name’. (See: John Burns, South Africa… Where Now? Supplement to International Cycle Sport magazine, 1976).

- Jowett’s claim that these were ‘South African’ championships is open to question as South Africa only became a unitary state in 1910 when the ‘Union of South Africa’ was formed. During the 19th century, the region consisted of British colonial territories (the Cape Colony and the Colony of Natal) and Boer republics (the Orange Free State and the Transvaal). The Anglo–Boer War took place between 1899 and 1902, ending in Boer defeat. It was only thereafter that moves were made towards establishing South Africa as a unitary state. According to the website ‘South African History Online’ (www.sahistory.org.za/) in 1907 the International Olympic Committee accepted that the four British colonies (Cape of Good Hope, Natal, Orange River Colony and Transvaal) could compete in the 1908 London Olympics under the umbrella name of ‘South Africa’. A South African team of 15, of whom 4 were cyclists, took part in the 1908 Games.

- According to Garth ‘Faggi’ Thompson, a leading local cyclist of the 1940s and the1950s, cinders for the athletics track were provided on a regular basis by the SA railways from the nearby steam locomotive sheds where Faggi himself worked. The 460 yards long cycling track was ideal for events based on the Imperial mile and fractions thereof like the 440yards (¼ mile) and 880 yards (½ mile).

- Alan Bannister partnered Reg Harris on the tandem in the 1948 London Olympics at which they won the silver medal being beaten in the final by the Italian pairing of Teruzzi and Perona. After a distinguished track racing career, Tommy Godwin served as the international British cycling team manager for several years.

- In 1952, a six–man British track team consisting of Tommy Godwin (captain), Wally Box, Lloyd Binch, Don Burgess, Ken Mitchell and Alan Geldard toured South Africa. They were followed in 1958 by the Italians Guiseppe Beghetto (world sprint champion) and Giacomo Zanetti.

- This information is derived from A. Jackson. 2003. Facts About Durban. Second edition. (p. 84).

- Currie’s Fountain sports ground acquired the reputation of being a centre of ‘non–racial’ sport in that all local people of colour were able to associate there in sporting activities. It also became a major place for protest meetings against the apartheid regime.

- This claim is made on the website (http://ancestry 24.com/history–of–cycling–in–south–africa/). [Accessed 23 Dec. 2010]. Since the Lords Ground track was demolished in 1954 and the Currie’s Fountain track was moribund, the S.J. Smith (‘Wema’) stadium’s track was the most likely venue. According to Jowett (op. cit.: 26):

‘(In) 1959 Application was made to the South African Cycling Federation for affiliation by the S.A.A.A.& C. Association. This was the independent Bantu Association and their action comprised a great break–through for the sport in South Africa.’

It is worth noting further that, writing in 1976, John Burns (op. cit. no page nos.) observed in this regard:

‘The Black South African cyclists’ organisation is a joint athletics and cycling federation: the South African Amateur Athletic and Cycling Federation. The sub–committee responsible for cycling has a White chairman and a White secretary. The president of the federation is a Black man…’

12 – Handicap cycle racing is generally associated with Australian cycling. However, as Reg Harris’ autobiography makes clear, handicap racing was an integral part of British track meetings both before and immediately after World War II (see: Harris [1976], esp. chapters 1–4). Handicap events make for ‘go all the way’ racing and develop the last gasp finishing skills which were to serve Harris so well subsequently in match sprinting. By their very nature, handicap track races encourage spectator involvement. J.B. Wadley wrote of track handicaps in The Raleigh Book of Cycling (1975:153–4):

‘Nearly all track riders start their careers by riding handicap races, the traditional distances being half–mile and one–mile. As newcomers they are given a “middle mark” by the handicapper. When a man has won a handicap final his allowance is reduced the next time…Most handicap–race winners emerge from the “middle–markers”…Occasionally a “long marker” with a generous allowance stays out in front until the finishing line but the real handicap hero is the “back marker” who starts on scratch and goes right through the field to victory’.

13 – Of handicap races, Simes (op. cit.: 142–144) writes:

‘The handicap race is a very good race to watch…The race can be any distance from a quarter mile up to several miles, but the better ones are very, very short. The limit riders, who have the shortest distance to travel, are spaced ten yards apart; closer to scratch there may be five yards between each man. The handicapping is usually done by the race director; if it is done right, all the riders come together right towards the end in a string and everybody’s trying to pass. It’s very spectacular…Usually, just as everyone comes together, it’ll be going into the sprint, so there’s not much sitting in…’

(Jack Simes was a key figure in the revival of competitive cycling in the United States in the 1960s and 1970s. He raced on both road and track as an amateur and a professional, contested the Olympics and then served as US national coach).

14 – Kings Park CC was the only Durban club entitled to use the Kings Park track during that period even when ‘…KPCC had only 16 licensed riders in May 1973’ (Huckett n.d.: 8).

References

Burns, John. 1976. South Africa… Where Now? Supplement to International Cycle Sport. UK: Kennedy Brothers.

Harris, Reg (with G.H Bowden). 1976. Two Wheels to the Top: The Autobiography of Reg Harris. London: W.H. Allen.

Huckett, Dave. No date. History of Kings Park Cycling Club. Unpublished.

Jackson, Allan. 2003. Facts About Durban. (Second edition). Durban: F.A.D. Publishers.

Jowett, Walter. 1982. Centenary: 100 Years of Organised South African Cycle Racing. South Africa: South African Cycling Federation.

Simes, Jack (with Barbara George).1976. Winning Bicycle Racing. Chicago: Contemporary Books.

Wadley, J.B. (Jock). 1975. ‘Cycle Sport–On the Track’. In R.C. Shaw (ed.) The Raleigh Book of Cycling. London: Peter Davies (pp.147–156).

Websites

(www.cyclingweekly.co.uk/news/latest/510343/ron-webb-the-big-interview.html)

[Accessed 16/12/2010]

(http://www.ancestry 24.com/history–of–cycling–in–south–africa/). [Accessed 23 Dec. 2010].

(http://www.sahistory.org.za/) [Accessed 27 Dec. 2010].

(http://www.ronwebbcycletracks.com/) [Accessed 30 Dec. 2010].

Posted: Sunday 23rd August 2020

This article appears in the following categories.

Upcoming Events

Whether you are looking for a gentle social meet up, or a 100-mile ride browse the community’s upcoming events and plan your next weekend outing.