Cycling Fashions and Fashionistas in Durban, South Africa in the 1950's & 1960's

Posted: Saturday 22nd August 2020

With its sunny, subtropical climate of mild winters and hot, humid summers, the east coast South African city of Durban is ideally suited for both leisure and competitive cycling all year round and this originally Victorian colonial city has long had its cycling enthusiasts. But the local popularity of cycling has waxed and waned over the decades and local fashions in lightweight bikes, equipment and cycling paraphernalia have undergone frequent changes, never more so than in the second half of the 20th century.

This article concentrates on the Durban cycling scene as it existed in the 1950s and 1960s with an emphasis on the competitive cycling ‘subculture’ of the time, focusing particularly on the lightweight equipment then in use locally(1).

Cycling in Durban in the 1950s

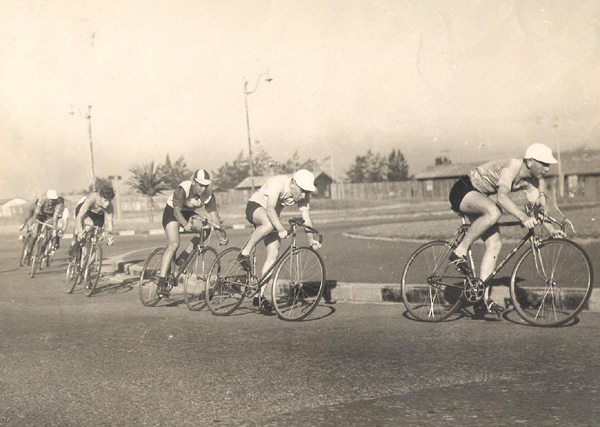

In the decade of the 1950s, competitive cycling in both Durban and nationally held under the auspices of the South African Cycling Federation (SACF) was organised into two ‘seasons’: a summer track racing season and a winter road season, with British–style time trials of 10, 25, 50 and 100 miles forming the staple winter diet interspersed with occasional ‘massed–start’ road races often run as handicap events. Not surprisingly, given this pattern, most local riders of the era relied upon a single fixed machine which they raced on the track in summer and in the winter road time trials. The generally flat time trial courses used at the time together with the shallow bankings of Durban’s 400 yards plus ‘Lord’s Ground’ cycle track were perfectly matched to the fixed wheel machines of the period.

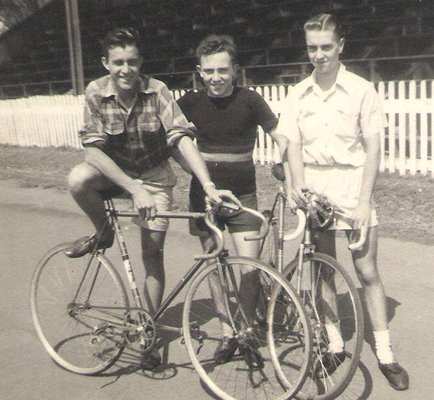

Classic Steel Framesets of the 1950’s

The steel framesets of the machines ridden by competitors in Durban during the 1950’s came from two main sources: Britain and Italy. Frejus and Legnano from Italy were extremely popular marques (the former typically finished in black enamel with twin gold bands on the seat tube trimmed with rainbow bands in honour of pursuiter Leandro Faggin, a matching gold head tube and chromed forks and ends; the latter available in metallic classic yellow/green but also in red and blue). From Britain, Claud Butler frames were very popular, the most eye–catching being fully chromed framesets covered with translucent coloured lacquers. But there were also others from small builders like A.W. Gillott and Hobbs of Barbican, in most instances brought back by local riders who had competed abroad. Carlton track framesets, most notably the ‘Flyer’, also featured prominently locally.

In terms of design, the Italian framesets were tighter, with minimal clearances, chunkier stays and built of Columbus tubing, making them generally heavier than their British counterparts which used Reynolds 531. These latter tended to have longer wheelbases and ‘gappy’ frames, often with pencil seat stays making them susceptible to whip under sprinting to the point where they would shed their (often block) chains. In short, the British framesets were more of the ‘Path’ type, designed for road time trials and smooth pursuit efforts rather than for the rigors of bunched track racing – some forks were even drilled to accommodate a front brake while others were fitted with Resilion cantilevers. However, despite such idiosyncrasies in design and handling, the British framesets were invariably beautifully finished with fancy lugwork neatly lined to highlight this, a range of exquisite ‘flamboyant’ colours and often with contrasting box lining trim.

French–built framesets and complete machines were never seen in Durban in the 1950s, although occasionally exotica turned up like a chromed Raleigh RRA (complete with 3–speed Sturmey Archer fixed hub gears), a Mexican–made Benotto (owned by top rider ‘Taffy’ Boyd) and a Belgian Plum Vainqueur (ridden by champion local sprinter Bruce Potter, finished in Plum’s traditional purple and yellow livery and – in retrospect – probably built for indoor racing on short tracks). As the 1950s progressed, made–to–measure DHC racing framesets, built in Johannesburg by German–born immigrant Hans Huth, became more commonplace locally. These were constructed from Reynolds 531 tubing and Nervex lugs and, with a design somewhere between the Italian and the British styles, eminently suited to local conditions. Huth also built Jowett–labelled frames for Jowett Cycles in Pietermaritzburg inland from Durban. As Frejus ceased production, Italian Cinelli frames appeared locally but these were uncompromisingly tight track frames.

Equipment of the 1950s

Various models of Brooks B17 leather saddles were de rigueur on Durban racing bikes of this period, which tended to be built up from a hybrid mix of British and Italian parts and fittings. Cottered steel cranks – Williams, Chater Lea, Magistroni and Gnutti – were the norm along with interchangeable steel rings and1/8–inch chains sometimes of the block type.

Anodised red and blue Airlite large flange hubs (often with one ball bearing removed from each side and run dry to give a precision–sounding tick) were much favoured along with Fiamme and Nisi tubular rims. Wheels were invariably spoked 32×40 with the spokes often being tied and soldered for greater rigidity and the spoke holes plugged with cork to facilitate the adhesion of tubulars using a home–made solution of shellac diluted in warmed methylated spirits. Dunlop tubulars were initially widely used (the silk–cased No.1s being reserved for track use only), but these were subsequently increasingly replaced by Italian–made Cléments.

Learning the mysteries of fitting, repairing and caring for tubular tyres along with gearing terminology – ‘88’ (inches) was the magic number for track racing – were integral parts of the initiation of the Durban sporting cyclist of the 1950s.

Changes in the local cycling scene

The late–1950s saw two major changes which had a profound effect upon the local cycling scene. The first was the demolition of the old Lord’s Ground track and the building of the new King’s Park stadium; the second was the growing popularity of ‘massed start’ road racing both locally and nationally.

The new pink cement Durban track, while still long by current standards (over 400 metres per lap), had 38 degree bankings at their maximum points and this, together with the new road racing craze, meant that the serious local cyclist now needed two machines: a dedicated track bike with a high bottom bracket and 165mm cranks and a multi–geared road bike.

While some locals remained single fixed–wheel purists they were a dwindling minority and a new breed of riders began to emerge who rode freewheel multiple gears on the road and a single fixed on the track.

Some riders of a mechanical bent even succeeded in modifying the right track rear end of their machines to accept a 3–speed derailleur mechanism and fitted these together with brakes for the winter road season, reverting to a single fixed in the summer!

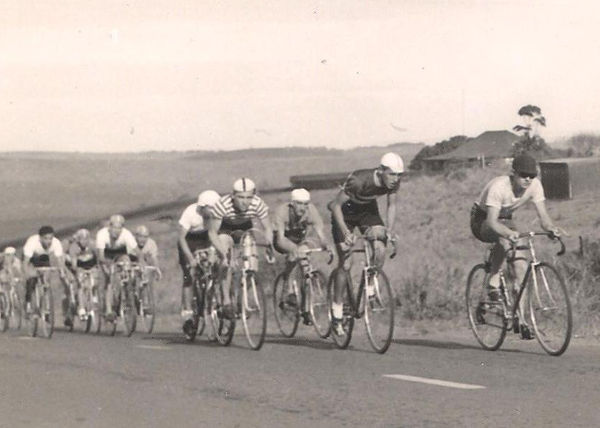

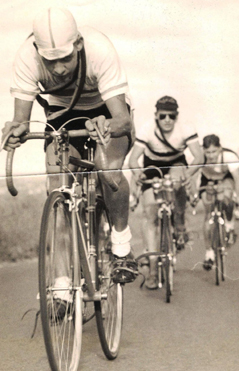

The road racing revolution

In the course of the 1950s, the institution of new ‘massed start’ road races, including stage races (the Ladysmith race, the Kokstad race, the ‘Old Dutch’ Durban –Johannesburg and the Cape Town–Johannesburg races were the most prestigious) created a demand for ‘real’ road machines complete with derailleur gears, brakes and water bottles as then ridden by BLRC riders in Britain and by European icons like Coppi, Bobet and Magni.

Local cycle dealers sought to meet the demand: Frejus, Legnano, Fiorelli, Viking, Sun, Carlton and the locally–produced DHC Cycles (subsequently rebranded as Deale & Huth, based in Johannesburg) and Jowett road framesets and complete machines began to proliferate. Table 1. lists some of the rarer road machines which graced Durban roads at the time.

Table1. Unusual road machines in Durban in the 50’s

| MAKE & MODEL | PROVENANCE | COMMENTS |

| Learco Guerra | Italy | Ridden by Gaul and Bahamontes in Europe ; silver grey, worlds bands |

| Viking 'Ian Steel' | Britain | Metallic Dark green, orange panels, Ian Steel signature on top tube |

| Viking Road Tandem | Britain | All-chrome, hub rear brake |

| Paris 'Galibier' | Britain | Novel tube format |

| Coppi | Italy | Silver, novel fork crown with Coppi logo, blue decals and trim |

| P T Stallard | Britain | Pale blue enamel, JUY 543 gear mech. |

| Holmes | Britain | Pale blue enamel |

| Dayton 'Roadmaster' | Britain | All-chrome, Simplex gears, GB brakes |

| Elswick 'various models' | Britain | Imported by S H Francis cycle dealers, flam finishes, box lining |

| Sun 'Wasp', Soliel d'Or | Britain | Imported by Peerless cycles, flam finishes |

| Cinelli 'Super Course' | Italy | Orange or white enamel, Campag ends, sloping fork crown, chrome lugs |

Road bike fittings and accessories

Initially, on the cusp of 1950, Osgears were commonly used on road machines (see image below). However these were soon succeded by Simplex and Cyclo Benelux front and rear derailleurs, the front changers being rod operated in both instances. Then in the latter part of the 1950’s, these were increasingly replaced by cable–controlled Campagnolo ‘Gran Sport’ front and rear changers particularly on Italian machines. The first alloy cotterless cranks to appear locally were French–made TAs and the standard double chain ring format was for 47/49 teeth with 3, 4 and ultimately 5 speed rear ‘clusters’ (mainly Regina) ranging from 14 to 21/22 teeth.

Brakes were generally alloy GB ‘Coureur’ or Universal side pulls, both with elegantly curved alloy levers and rubber hoods. Italian Ballila and French Alp brakes and Mafac centre pulls were much–admired rarities. When centre pulls arrived they were by Universal, GB, Weinmann and CLB.

Handlebar stems and handlebars – the former in alloy or steel, the latter in alloy – were variously GB, Cinelli, Ambrosio or Magistroni with GB Maes and Cinelli ‘Campione del Mondo’ Model 64 ‘bars being much favoured. The ‘bars themselves were cloth taped.

Unica Nitor lightweight plastic saddles proliferated, replacing leather, and high pressure rims fitted with Dunlop high pressure tyres challenged the ubiquitous sprints and tubulars as they were cheaper and more durable, if much heavier, alternatives. Campag quick release hubs, both small and large flange, rapidly became de rigueur on road bikes.

Pedals with toe clips and straps (preferably by Christophe and Binda, respectively) along with cycling shoes (ideally by Detto Pietro) fitted with shoe plates – always difficult to position correctly – were essential accessories for the dedicated Durban cyclist of the period.

High pressure alloy pumps by Bluemels and Zefal anodised in a variety of colours along with equally colourful anodised alloy water bottles by Coloral in REG wire cages with sprung clips were the norm. Further accessories included mechanical Cyclo mileometers/odometers, fitted to the front wheel and forks.

Clothing of the era

Cycling shorts, black knit and preferably by Worthy, were the norm, with shiny ‘silk’ jerseys for the track while for the road jerseys were in various knitted fabrics with pockets at the rear. Jerseys in club colours became popular amongst members of the three local clubs: ‘Mayville CC’ (blue and white), ‘Albion Harriers’ (red, yellow and black) and ‘Durban CC’. (black, red and white). In the late–1950s, the Mayville CC adopted the name ‘King’s Park CC’ with the advent of the new track but the other two both subsequently disbanded. Club membership was a prerequisite for obtaining a racing licence issued by the SACF, under the auspices of which, through its provincial body the Natal Cycling Union (NCU), local races on both road and track were run. Strict race rules applied to ‘advertising’ on cycling apparel in the form of logos and even small brand labels – some martinets in the ranks of local cycling officialdom were still applying these draconian ‘rules’ in the 1980s! However, imported jerseys embroidered with logos like Fiorelli and Frejus were obtainable from local dealers and were common on club runs.

Crash hats of the ‘hairnet’ or ‘Danish’ type, consisting of padded narrow strips, were compulsory for track racing but not used for either road races or time trials where white cotton cycling caps (sans logos but with coloured stripes) were favoured. Cycling mitts with crocheted backs were widely used and white socks complementing the black cycling shoes completed the outfit of the Durban cycling fashionista of the 1950s.

The Durban Cycling Scene in the 1960s

On weekend club runs throughout the 1950s, the paths of two groups of Durban cyclists often crossed and both groups eyed each other cautiously but had little contact. The one group, all mounted on track bikes ‘of a certain age’, were Africans belonging to the South African Railways and Harbours (SAR&H) sports association who competed exclusively on the Umlazi track near their segregated hostel accommodation in south Durban; the other group, mounted mainly on state–of–the–art road bikes, were Durban’s white cycling fraternity who competed separately under SACF rules at the Kings Park track and on public roads.

This was the ‘era of apartheid’ in South Africa during which ‘race’ determined all else, including sporting activities (2). During the 1950s, with the SACF being affiliated to the UCI, (white) South African cyclists competed quite freely internationally, with several winning medals at both British Empire and Olympic Games and also participating in UCI World Championships. Little did those on their respective club runs in Durban in the 1950s realise, however, that the local cycling bubble was about to burst.

International sporting boycotts of South Africa because of apartheid in sport, including cycling, began in the 1960s and gathered momentum to the point where the SACF and, more broadly, South African competitive cycling was effectively to remain internationally isolated until the end of apartheid in the mid–1990s (3).

As SACF–governed competitive cycling became increasingly isolated internationally, its contacts with the wider cycling world became more tenuous, erratic and furtive to the point where foreign riders were even persuaded to use aliases to compete in SACF–organised events in South Africa and SACF–affiliated riders did the same to compete abroad(4).

Both the sporting boycott and the trade embargoes imposed on South Africa because of apartheid also impacted dramatically upon the lightweight cycles and components available to Durban cyclists in the 1960s. With declining opportunities to compete abroad, fewer cutting–edge machines and less innovative equipment were brought onto the local scene by returning riders and officials; with trade embargoes, the steady stream of imports by dealerships suffered interruptions.

Instead, job lots began to appear in ad hoc batches at local bike shops and were snapped up by local enthusiasts. For instance, Peerless Cycles in Durban imported a consignment of Urago framesets and machines – the first lightweights ever to arrive in Durban from France. Subsequently, Zeus road and track machines and framesets were introduced from Spain, along with Zeus components (gears, chain sets, hubs and pedals). RIH framesets from the Netherlands also arrived and enjoyed some vogue. Supplies of Campagnolo’s growing range of components (brakes, cotterless chain sets, and pedals) filtered onto the local market in dribs and drabs but were often in short supply as were spares like brake blocks. Early Shimano quick release hubs were first imported by Shimwell’s, a Durban agent for Shimano fishing reels.

Local lightweight steel frame building enjoyed something of a boost. That unfinished tube sets and lugs could be more readily imported without attracting undue attention from embargo monitors probably played its part in this as did the coincidental decline in the number of small specialist frame builders in the UK and elsewhere during this decade. During the 1960s, therefore, locally-built DHC/Deale & Huth framesets and Jowett framesets enjoyed a boom – a phase stimulated further by both builders sponsoring local ‘independent’ teams in 1963 and 1964. While both of these makers subsequently ceased production, they presaged the later local manufacture on a larger scale of Peugeot and Lejeune framesets under licence from their French parent companies.

Retrospective: Where are they now?

Little trace remains today of the lightweight cycles, framesets, equipment and apparel which were in vogue in the Durban of the 1950s and 1960s.

Undoubtedly Durban’s highly–corrosive humid, subtropical climate is partly to blame, leading steel frames to rust away and alloy components to oxidise, especially if they were not originally anodised. But the fickleness of fashion also surely played an important part in this. Acceptance into any cycling inner circle requires that one constantly keeps ‘looking the part’ – in short, that one be a cycling fashionista. The joshing of fellow riders, the cachet of having the ‘latest’ and the fact that top riders are already at this technological cutting edge are seductive inducements to even the most modestly–talented of sporting cyclists to follow current cycling fashions, discarding the ‘obsolete’ along the way.

It is therefore indeed fortunate for those cyclists who – like me – find themselves caught in a 50s/60s time warp that it has become increasingly fashionable in the 21st century to be a retro connoisseur who, like the quintessentially French Marcel Proust, indulges in the unashamedly nostalgic ‘remembrance of (cycling) things past’.

More on the effect of apartheid on the cycling scene in Durban

FOOTNOTES

1) The article draws primarily upon my own experiences and recollections as an enthusiastic cyclist in Durban in the 1950s and subsequently (with a spectacularly undistinguished competitive record) and is therefore largely an ‘oral history’. However, it is also based on the reminiscences shared in a series of later conversations (‘interviews’ is too formal a term for them) with a number of other local cyclists and aficionados from that era including most notably Garth ’Faggi’ Thompson, Brian ‘Taffy’ Boyd, Maurice Chelin, the late Dick Ronaldson and the late Bob Turk. The work, Centenary: 100 years of organised South African cycle racing, (1980), compiled by W. Jowett and published by the South African Cycling Federation, proved invaluable as a source of factual information. The websites ‘Classic Lightweights’ and ‘Classic Rendezvous’ have been mined for further technical information. Ultimately, however, I am solely responsible for any inadvertent distortions, errors, ‘senior moments’ and omissions evident in the article.

2) To the best of my knowledge, the history of segregated black cycling in South Africa in the 20th century remains undocumented. Scattered archival and anecdotal evidence exists concerning cycling tracks on many South African gold mines which were used exclusively by migrant African mine workers. Track cycling reportedly flourished amongst the Coloured community in towns of the Western Cape like Paarl and subsequently (in the 1970s) the South African Cycling Association (SACA) promoted non–racial cycling. Anecdotal evidence is of a Coloured cyclist originally from Cape Town who raced as a professional in 6–day indoor events in Europe during the 1950s. Jowett’s official SACF history contains only a few very cryptic allusions to such matters.

3) South Africa was excluded from competing at the 1964 Tokyo Olympics and subsequently, and then from the Commonwealth Games. In 1970, the UCI suspended the SACF sine die. (See: Jowett, 1980:13).

4) In the 1970s a team of riders from Ireland competed in the SACF–run Rapport Tour stage race using pseudonyms. To quote from a report in Cycling Weekly (March 6, 2008:6): ‘Pat McQuaid, the president of the Union Cycliste Internationale…is no stranger to defying clearly defined rules…more than 30 years ago…in 1975 the Irishman was part of a team…that rode the Rapport Tour in South Africa…the race was not approved by the UCI because South Africa was an outcast from the international community. The anti–apartheid agreement barred relations with the country. McQuaid raced under a false name–as did Sean Kelly–and was banned from the 1976 Olympics.’ (The 1974 Rapport Tour was won by the late Arthur Metcalfe from Britain, riding an MKM [Metcalfe–Kitching–Mason] machine. At the time, MKM framesets were being imported into South Africa in small numbers by a Johannesburg dealer).

Posted: Saturday 22nd August 2020

This article appears in the following categories.

Upcoming Events

Whether you are looking for a gentle social meet up, or a 100-mile ride browse the community’s upcoming events and plan your next weekend outing.