A roller coaster ride: A fact file on cycling at the Olympic Games

Posted: Tuesday 18th August 2020

The important thing in life is not the victory but the contest; the essential thing is not to have won but to have fought well.

Baron Pierre de Coubertin (1863–1937). Founder of the modern Olympic Games.

Speech delivered at the Fourth Olympiad, London 1908.

Introduction: Cycling at the modern summer Olympic Games

Since 1896 a total of 27 modern summer Olympic Games have been held at regular four year intervals. The exceptions were during WWI and WWII. Cycling competitions have featured at every one of these 27 Games held between 1896 and 2012. However, there have been many variations and changes in the Olympic cycling programme down the years. Controversies have surrounded many of these as well as certain participants and the outcomes of specific events. In short, Olympic cycling has been a rollercoaster ride.

This fact file traces milestones in Olympic cycling contests down the years in point form. It first identifies different eras in Olympic cycling history and then explores each of these in further detail.

Five distinct historical periods are evident in cycling at the Olympics. These, together with the date and location details of their constituent Games, are:

- The ‘Originals’ (1896–1912): 1896 Athens; 1900 Paris; 1904 St. Louis; 1908 London; 1912 Stockholm [Total: 5]

- The Interwar Games (1920–1936): 1920 Antwerp; 1924 Paris; 1928 Amsterdam; 1932 Los Angeles; 1936 Berlin [Total: 5]

- The Post–WWII Games (1948–1960): 1948 London; 1952 Helsinki; 1956 Melbourne; 1960 Rome [Total: 4]

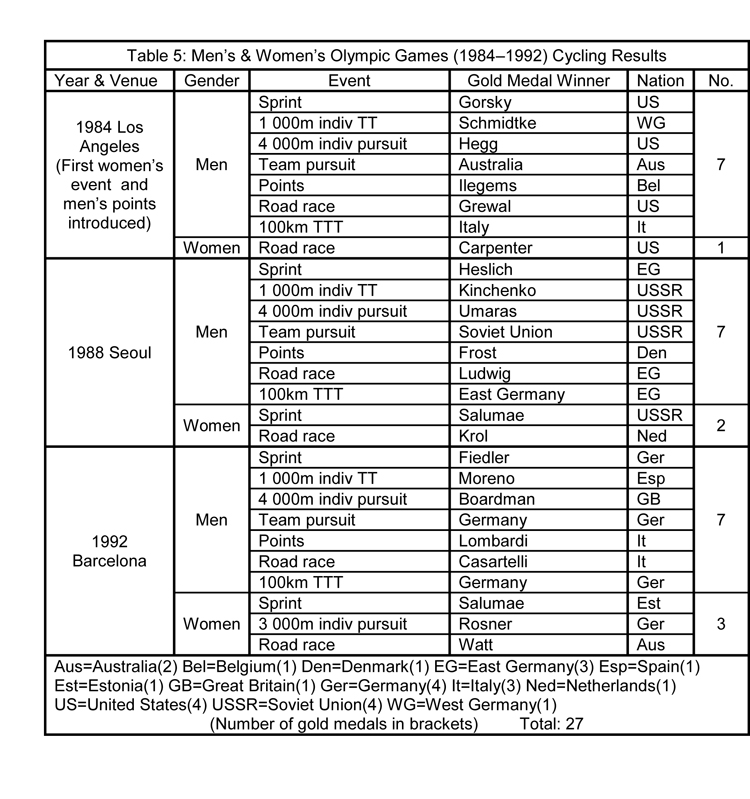

- The Cold War Games (1964–1992): 1964 Tokyo; 1968 Mexico City; 1972 Munich; 1976 Montreal; 1980 Moscow; 1984 Los Angeles; 1988 Seoul; 1992 Barcelona [Total: 8]

- The ‘Open’ Games (1996–2012): 1996 Atlanta; 2000 Sydney; 2004 Athens; 2008 Beijing; 2012 London [Total: 5]

What follows are details of the Olympic cycling competitions in each one of these periods.

The Original Games (1896–1912)

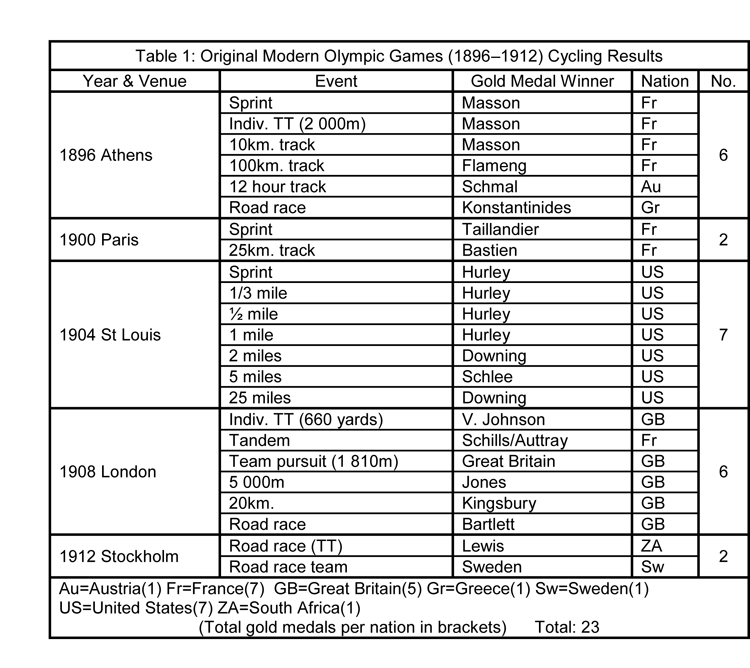

Table 1 is a summary of the cycling competitions held at the five Games held during this period.

The cycling programmes over these five Games varied widely. Virtually all they had in common was that the events were limited exclusively to amateur male cyclists. Many of the Olympic cycling events contested in this period were unique to only one Games programme, thus:

- The first Games in 1896 included a 12hr. track race.

- At St Louis in 1904 all the events were based on the Imperial mile and there was no road race.

- At Stockholm in 1912 the road race was a 320km. individual time trial in which the 126 riders started at two minute intervals beginning at 2 a.m.

- The Olympic cycling events at Paris 1900 were contested over a period of several months as part of a ‘World’s Fair’ and were mixed in with events that included professionals. This occurred at a time when the governance of world cycling was in crisis, ultimately resulting in the founding of the UCI (Union Cycliste International) in 1900.

- At St Louis in 1904 the cycling events had only American competitors who totalled 18 riders.

- The track cycling events at London 1908 were contested at White City. At these the sprint event was declared null and void when the competitors exceeded the stipulated time limit.

- The Games organisers of Stockholm 1912 did not want to stage any cycling events at all. Only after other nations protested was the road race hastily included but no track events were arranged.

- The Stockholm 1912 road race was won by the South African Rudolph ‘Okey’ Lewis in a time of 10:42:39 for the 320km. individual TT. It was the first and only time that a South African has won an Olympic gold in cycling. Freddie Grubb (GB) won the silver medal in 10:51:24.2 and Carl Schutte (US) the bronze in the event in 10:52:38.8. The British multi–world champion Leon Meredith finished fourth.

WWI (1914–1918) decimated the ranks of early 20th century cyclists. Few who survived were to return to competitive cycling after the war.

The Interwar Games (1920–1936)

We swear we will take part in the Olympic Games in a spirit of chivalry, for the honour of our country and for the glory of sport. Original Olympic Oath (first taken by competitors at the 1920 Antwerp Games)

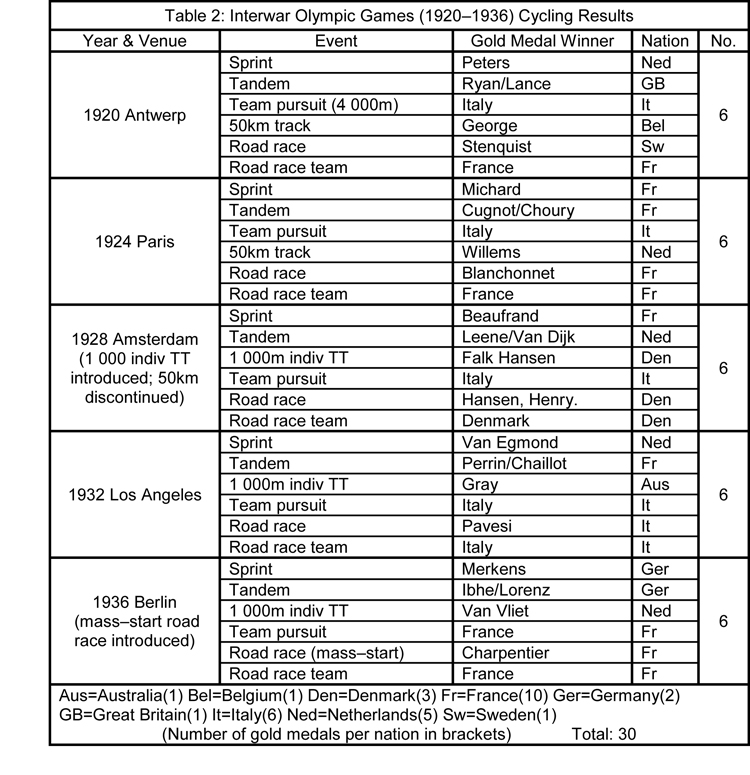

During the interwar period the cycling programme of events held at successive Olympics exhibited stability and continuity. This was in marked contrast to the situation which had prevailed during the pre–war original Games. Table 2 provides details of Olympic cycling contests during the interwar period.

- At the 1920 Antwerp Games the British pair of Thomas Lance and Harry Ryan won the gold in the tandem event. They were the last British riders to do so for 72 years until Chris Boardman won the gold medal at Barcelona 1992 in the 4 000m individual pursuit.

- From 1920 to 1932 the Olympic road race took the form of a long distance individual time trial with individual times being aggregated to decide on the team medals.

- The interwar Olympic road races run as individual TTs (!920–1932) served to produce several controversies:

- At Antwerp 1920 the fastest actual time for the 100 mile event – 4:41:26.6 – was set by Henry Kaltenbrun (South Africa). However, an objection was lodged by the Swedish rider Harry Stenquist who was delayed by a closed railway level crossing gate on the course. Olympic officials deducted four minutes from Stenquist’s actual time and awarded him the gold medal in a corrected time of 4:40:01.8, relegating Kaltenbrun to the silver medal position.

- At Amsterdam 1928 a debate arose surrounding the times set by the leading British time triallist Frank Southall and the Danish rider Henry Hansen. Hansen finished the 165km (102 ½ miles) course in a time of 4:47:18 to win gold while Southall took silver in 4:55:06. However, the British camp questioned the result, alleging that the Dane must have taken a short cut. This was because at 50km Southall had been only 90 seconds behind Hansen yet by the finish he had inexplicably conceded nearly 8 minutes. The British appeal was rejected and the original result was confirmed.

- While relatively few changes were made to the Olympic cycling programme during the interwar period, those which were proved significant.

- The 50km track event was held at Antwerp 1920 and Paris 1924 but discontinued thereafter.

- At Amsterdam 1928 the 1 000m individual time trial was introduced and was won by the Dane Willy Falk Hansen in a time of 1:14.2. It was included in the following 18 Olympics but discontinued after Athens 2004.

- Up to and including Los Angeles 1932 the road race was contested as an individual time trial with the team medals for this event being based on the aggregated times of a nation’s first four finishers.

- At Berlin 1936 the road race was changed to a mass–start event with the inaugural race being won by the Frenchman, Robert Charpentier. It remained a mass–start event thereafter with the team medal being based on aggregated time.

- Italy won the 4,000m team pursuit at four of the five interwar Olympics (1920–1932). France won the event at Berlin 1936.

- At Paris 1924 the track events were held at the Vel d’Hiv, making it the first Olympics at which an indoor track was used.

- At Los Angeles 1932 the 1000m TT gold was won by the Australian Dunc (Duncan) Gray in an Olympic record time of 1:13.0. He was the first Australian to win an Olympic cycling gold medal after finishing third in the same event at Amsterdam 1928.

- The Berlin 1936 Olympics were marked by controversy in the cycling match sprint final between Toni Merkens (Germany) and Arie Van Vliet (Netherlands). In the first round of the final Merkens impeded Van Vliet but was fined 100 marks rather than being disqualified. Merkens won the second round and with it the Olympic sprint gold medal. Van Vliet went on to win the 1000m TT gold at the Berlin Games.

- Over the course of the five interwar Olympics the cycling events were dominated by France (10 gold medals), Italy (6 gold medals) and the Netherlands (5 gold medals).

The Post–WWII Games (1948–1960)

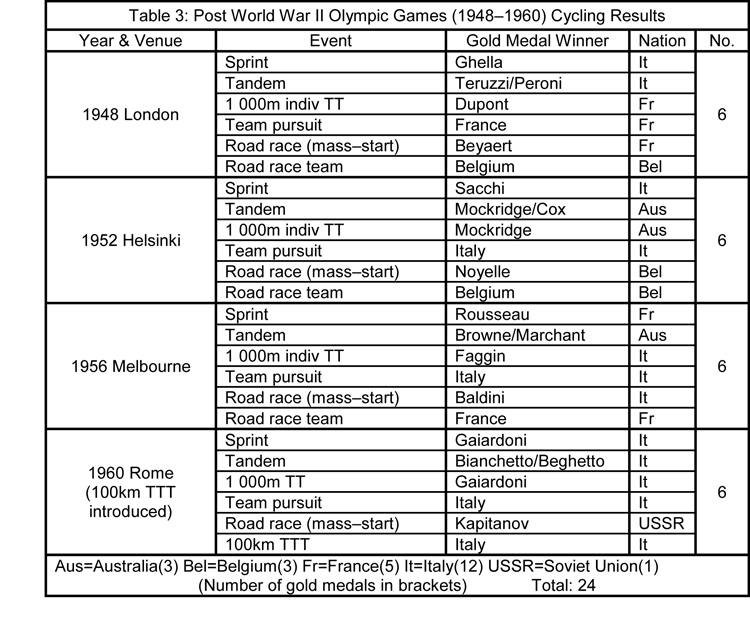

The four Games of this era retained the same cycling programme that had evolved during the interwar period with a total of six medal events being contested at each. The only change was the introduction of the 100km road team time trial at Rome 1960.

At London 1948 – the ‘Austerity Games’ – it was anticipated that the home favourite and reigning world amateur sprint champion, Reg Harris, would win the match sprint gold medal. It came as a shock, therefore, when Harris was beaten in the sprint final on the outdoor Herne Hill track by the Italian teenager Mario Ghella in two straight races. Harris also won silver in the tandem event with partner Alan Bannister. Ghella went on to win the UCI world amateur sprint title in 1948 on the Amsterdam 1928 Olympic track.

The cycling honours at the four post–WWII Games were dominated by Italy, winning a total of 12 gold medals followed by France with 5 golds.

Australian cyclists performed well at Helsinki 1952. The tandem gold was won by the pairing of Russell Mockridge and Lionel Cox. Mockridge also won gold in the 1 000m individual TT while Cox was second to Enzo Sacchi in the match sprint.

At Helsinki 1952 another challenge came from the southern hemisphere with South Africans Ray Robinson and Tommy Shardelow taking silver in the tandem and the SA pursuit team finishing second to Italy’s gold.

Italian cyclists were prominent at Melbourne 1956, winning three of the six Olympic golds contested. The Australian pair of Joey Brown and Anthony Marchant won the tandem event.

The Melbourne 1956 road race was won by Italy’s Ercole Baldini who later in the same year set a new world hour record of 46.394km. Alan Jackson (GB) took the bronze medal in the 1956 road race. Baldini later turned pro and won both the Giro d’Italia and the UCI world pro road championship in 1958.

Italian cyclists were again dominant at Rome 1960, winning five of the six cycling golds including the inaugural 100km. road team time trial.

The prestigious Rome 1960 road race was won by the Russian, Viktor Kapitanov. This was the first Olympic cycling gold medal to be won by the Soviet Union. It presaged later developments.

The Cold War Games (1964–1992)

Sport was an important way in which the communist nations of Eastern Europe asserted themselves during the Cold War, and cycling was one of the key disciplines … By the 1970s Poland, the Soviet Union and East Germany all boasted ‘amateur’ cycling teams … with full–time cyclists whose ’jobs’ were often military.

William Fotheringham (2010). Cyclopedia. p.122.

There were two distinct eras in Olympic cycling during this period:

1) Tokyo 1964–Moscow 1980: the era of the ‘shamateur’

2) Los Angeles 1984–Barcelona 1992: the advent of Olympic women’s cycling.

Tokyo 1964–Moscow 1980: the ‘shamateur’ era

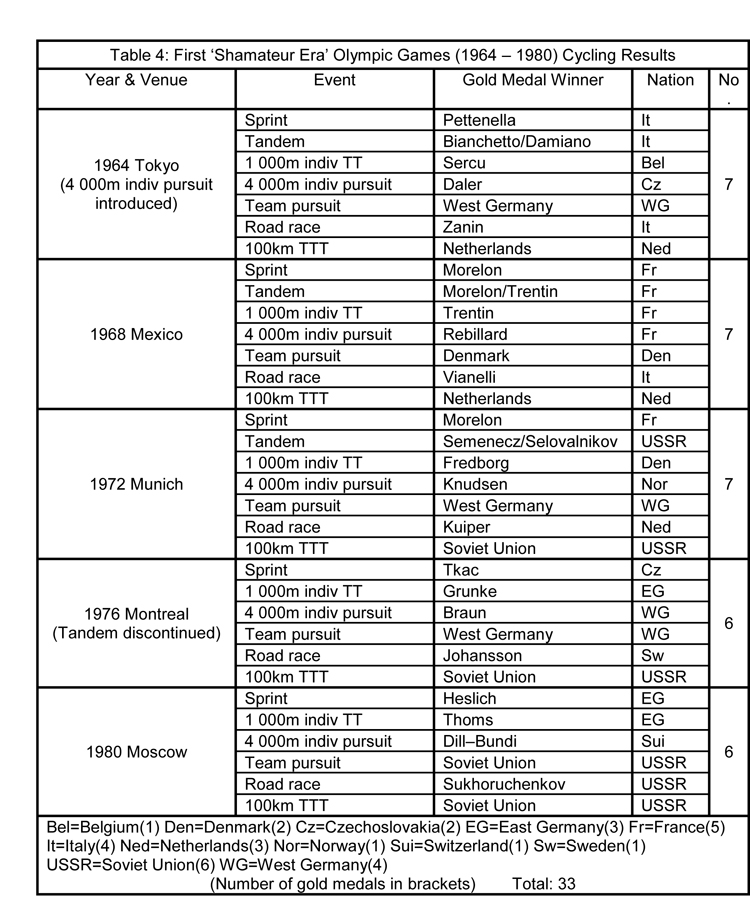

During the Cold War, ‘shamateur’ was the pejorative term applied in the West to sportspeople from the Eastern Bloc countries who, while officially ‘amateur’, were in reality full–time athletes. They rose to prominence in competition against western amateur sportspeople, most notably in international contests like the Olympic Games. Table 4 details the Olympic cycling results of this era.

At Tokyo 1964 the 4000m individual pursuit was introduced for the first time. The inaugural event was won by Jiri Daler of Czechoslovakia. It rapidly became a blue riband title. It was to continue as an Olympic event for 12 Games but was discontinued after Beijing 2008.

Patrick Sercu (Belgium) who won the 1000m individual TT at Tokyo 1964 went on to enjoy a glittering professional career on both road and track. He was twice world pro sprint champion (1967 and 1969) and won many six day races.

At Tokyo 1964 the reigning world amateur road champion Eddy Merckx (Belgium) dominated the Olympic road race. However, when in a small breakaway group approaching the finishing straight Merckx was controversially brought down by another rider in a crash on the final corner. He finished unplaced. Mario Zanin (Italy) won the mass sprint for the gold medal. Merckx turned professional shortly afterwards.

Eastern Bloc dominance of Olympic cycling gathered momentum during this period. At Moscow 1980 five of the six gold medals were won by riders representing East Germany and the USSR.

Hennie Kuiper (Ned) who won the Munich 1972 road gold became a successful pro roadman. This included winning the world pro road championship in 1975.

At Montreal 1976, where the track events were contested on an indoor track for the first time since Paris 1924, the tandem event was discontinued. It had been contested in 13 previous Olympics beginning with London 1908.

Daniel Morelon of France won the match sprint gold at two Olympics: Mexico 1968 and Munich 1972. He thus became the first person to win two Olympic sprint titles. (This feat was later repeated by the woman sprinter, Erika Salumae). At Mexico 1968 Morelon also won tandem gold with partner Pierre Trentin.

In the sprint final at Mexico 1968 Morelon set an Olympic record for the final 200m of 10.68 secs. At the same Games in winning the gold medal Trentin set an Olympic record in the 1 000m individual TT of 1:03.91. The tandem pairing of Morelon and Trentin achieved a final 200m time of 9.83 secs in beating Jansen and Loevesijn (Ned) for the gold. These times were achieved on an outdoor track at the high altitude of Mexico City. It was the thinner air at this altitude which subsequently attracted both Eddy Merckx and Francesco Moser to successfully attack the world hour record in Mexico City.

In Olympic cycling during this period East–West rivalry was reflected in the gold medal tally. This was headed by the USSR (6 golds) followed by France (5 golds), Italy (4 golds), West Germany (4 golds) and East Germany (3 golds).

2. Los Angeles 1984–Barcelona 1992: the advent of Olympic women’s cycling

There is still no category for women riders in the Olympics. This should be changed. R. Watson & M. Gray (1978) The Penguin Book of the Bicycle. p.236

While the UCI first introduced women’s title events into its annual world championships in 1958, as the above quote indicates, in the 1970s Olympic cycling still remained an exclusive male preserve. It was to be 26 years before the Olympics admitted women’s cycling at Los Angeles 1984.

In 1958 the UCI instituted three women’s world championships: a mass–start road race together with the match sprint and the 3000m individual pursuit on the track. Russian women dominated the sprint event for two decades. Galina Ermolaeva (USSR) won the first four women’s world sprint titles (1958–1961) and was succeeded by her compatriots Savina and Tsareva who both became multiple world sprint title winners. The first woman to win the road world title was Elsy Jacobs (Luxembourg) to be followed in subsequent years by Yvonne Reynders (Belgium) and Beryl Burton (GB). Although Lydia Kochetova (USSR) won the first UCI world pursuit title, it was an event which Beryl Burton dominated, winning the title five times in the period up until 1966. Thereafter a succession of Russian women proceeded to win the event.

In contrast to the UCI, the IOC delayed the inclusion of women’s cycling at the Olympic Games until the 1980s and even then kept it to a minimum. The initial breakthrough came at Los Angeles 1984. However, at these Games women’s cycling was confined to a single event: a road race. The gold medal winner was Connie Carpenter (US), a former speed skater, who outsprinted her team mate Rebecca Twigg for an historic victory.

- Over the course of the three Games in this period, women’s cycling events gradually increased from one at LA 1984 to two (match sprint and road race) at Seoul 1988 and three (match sprint, 3000m individual pursuit and road race) at Barcelona 1992.

- The collapse of the Eastern Bloc in the late 1980s is reflected in the Olympic cycling results of this period. Cycling at Seoul 1988 was dominated by riders from the Eastern Bloc. Male riders from the USSR and East Germany won three gold medals each. Erika Salumae (USSR) won the women’s match sprint title in 1988. She won it again at Barcelona 1992 but representing post–USSR Estonia.

- At Los Angeles 1984 the men’s points race was introduced and continued for four subsequent Olympics. The 1984 title was won by Roger Ilegems (Belgium).

- At Barcelona 1992 Chris Boardman became the first British cyclist to win Olympic gold in 72 years when he triumphed in the 4000m individual pursuit. In the final, Boardman, riding an aerodynamic Lotus machine caught and passed his opponent, Jens Lehman (Germany).

The ‘Open’ Games (1996–2012)

Two phases are evident in Olympic cycling during this period:

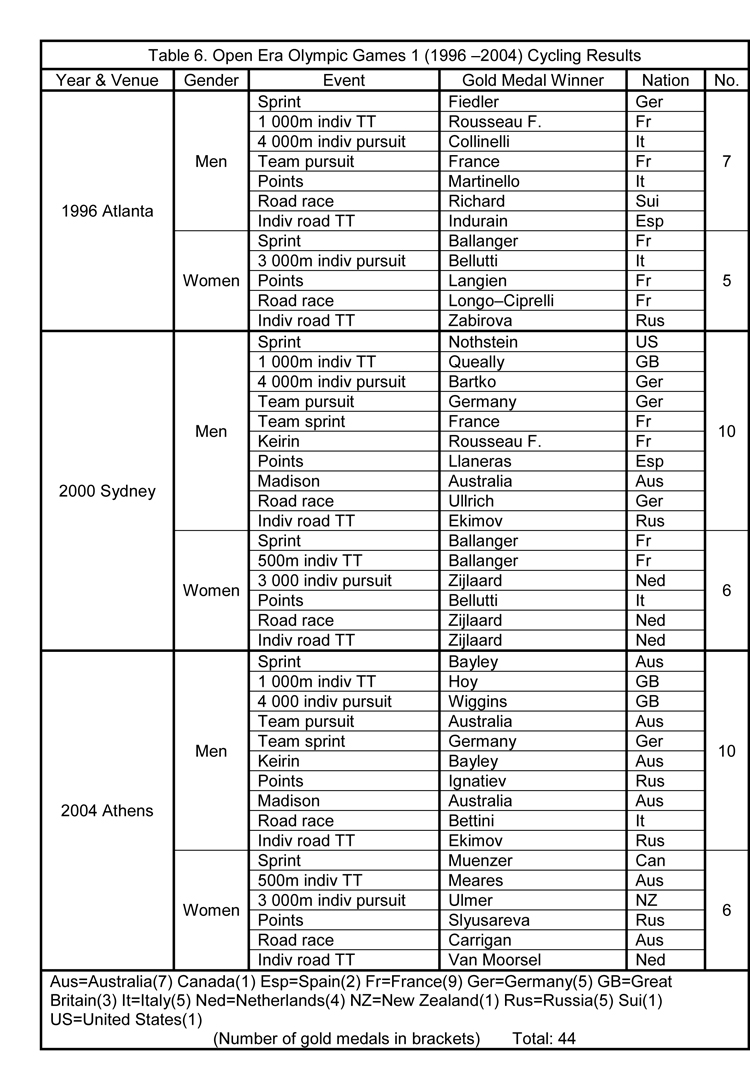

- The Expansionist era (1996–2004)

- The ‘Team GB’ Games (2008 – 2012)

1. The Expansionist era in Olympic cycling (1996–2004)

Following Barcelona 1992, the IOC abandoned its longstanding distinction between amateurs and professionals and the UCI followed suit. As a result the 1996 Atlanta Games were ‘open’ to all cyclists. In the process the Games cycling programme was progressively enlarged and modified during this phase (See Table 6).

At Atlanta 1996 the men’s road team TT was replaced by the men’s individual road TT. The inaugural event was won by Miguel Indurain (Spain), who was the leading professional roadman of his era.

At Atlanta 1996, the women’s cycling events were increased to 5 with the introduction of the track points race and an individual road TT.

At Sydney 2000, the men’s events were increased from 7 to 10 titles and the women’s from 5 to 6.

The three new men’s track events introduced at Sydney 2000 were the Team Sprint, Keirin and the Madison.

The women’s 500m individual TT was added at Sydney 2000.

At Sydney 2000 the men’s road race was won by Jan Ullrich (Germany) whose career was subsequently blighted by proven drug use. The silver medal was won by Alexander Vinokourov (Kazakhstan), another rider found drug–positive. (Vinokourov returned aged 38 to win gold in the London 2012 road race).

At Athens 2004 the same ten titles for men and six titles for women as at Sydney 2000 were contested.

At Sydney 2000 the men’s individual road TT was won by the Russian, Viatcheslav Ekimov. After the American Tylor Hamilton tested positive for drugs, the Athens 2004 gold medal he was awarded for the road TT was retrospectively awarded to Ekimov who had finished second. Ekimov thus now holds two successive gold medals for this event.

The Expansionist era in Olympic cycling (1996–2004)

Following Barcelona 1992, the IOC abandoned its longstanding distinction between amateurs and professionals and the UCI followed suit. As a result the 1996 Atlanta Games were ‘open’ to all cyclists. In the process the Games cycling programme was progressively enlarged and modified during this phase (See Table 6).

- At Atlanta 1996 the men’s road team TT was replaced by the men’s individual road TT. The inaugural event was won by Miguel Indurain (Spain), who was the leading professional roadman of his era.

- At Atlanta 1996, the women’s cycling events were increased to 5 with the introduction of the track points race and an individual road TT

- At Sydney 2000, the men’s events were increased from 7 to 10 titles and the women’s from 5 to 6.

- The three new men’s track events introduced at Sydney 2000 were the Team Sprint, Keirin and the Madison.

- The women’s 500m individual TT was added at Sydney 2000.

- At Sydney 2000 the men’s road race was won by Jan Ullrich (Germany) whose career was subsequently blighted by proven drug use. The silver medal was won by Alexander Vinokourov (Kazakhstan), another rider found drug–positive. (Vinokourov returned aged 38 to win gold in the London 2012 road race).

- At Athens 2004 the same ten titles for men and six titles for women as at Sydney 2000 were contested.

- At Sydney 2000 the men’s individual road TT was won by the Russian, Viatcheslav Ekimov. After the American Tylor Hamilton tested positive for drugs, the Athens 2004 gold medal he was awarded for the road TT was retrospectively awarded to Ekimov who had finished second. Ekimov thus now holds two successive gold medals for this event.

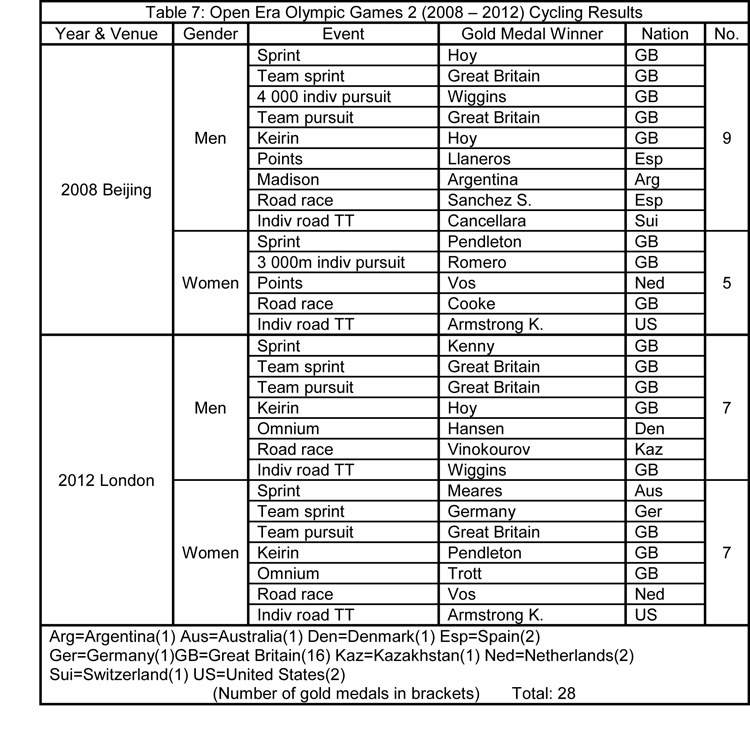

2. The ‘Team GB’ Games (2008 – 2012)

Improvements in British track cycling performances at the Olympics continued in the wake of Boardman’s gold at Barcelona 1992. At Sydney 2000 Jason Queally (GB) won the 1000m individual TT. Then at Athens 2004 Chris Hoy won gold in the same event and Bradley Wiggins took the gold medal in the individual pursuit. However, Team GB’s major breakthrough came at Beijing 2008 where the team won gold medals in eight of the 14 cycling events. Five golds were won by British men and 3 golds by British women Clearly British competitive cycling had undergone a transformation. This is directly traceable to the advent of a cycling performance programme generously funded largely by the British national lottery.

Taking advantage of the scrapping of the amateur/professional distinction by the IOC and UCI, in 1997 the sponsored ‘World Class Performance Plan’ for cyclists was instituted in Britain. In a manner reminiscent of the of the Eastern Bloc cycling academies during the Cold War, an elaborate structure of training centres, development programmes, coaches, sports psychologists, nutritionists and technical advisors were assembled to develop British cyclists into world beaters. The results at Beijing 2008 vindicated the British programme and those from London 2012 served as further confirmation (see Table 7). Nevertheless, there were a number of controversies.

- At Beijing 2008 the cycling programme was scaled back by discontinuing the men’s 1 000m individual TT and the women’s 500m individual TT. Eliminating the men’s event was particularly controversial as it had a long Olympic history, having been first introduced at Amsterdam 1928 and won by many iconic track cyclists down the years. These included Falk Hansen, Dunc Gray, Van Vliet, Mockridge, Faggin, Sercu, Trentin, Fredborg and Hoy.

- At London 2012 the cycling programme was radically revised and new restrictions on the number of entries per nation were introduced. On the track, entries were limited to one competitor or team per nation.

- At London 2012, while parity was achieved in the number of events for both men and women, the number of medal events was reduced to seven each. This was achieved by introducing a composite ‘omnium’ title for both men and women. This consisted of a number of events for which points are awarded, the winner being the rider with the best points tally overall.

- In British cycling circles it was widely believed that the new reduced Olympic track programme and the limitations on riders per nation at London 2012 were the result of an IOC/UCI conspiracy to undermine the British dominance of Olympic cycling.

- At London 2012, British riders won 8 of the gold medals out of a possible 14. In so doing they were hailed in Britain as triumphing over the IOC/UCI conspiracy.

- Karen Armstrong (US) won the women’s individual road TT at both Beijing 2008 and London 2012 while Chris Hoy (GB) did the same in the men’s Keirin.

- Aleksander Vinokourov’s victory in the London 2012 men’s road race received a mixed reception as he had previously been subject to a competition ban for testing positive for using illicit substances. Home favourite Mark Cavendish (GB) finished outside the medals.

- The British trio of Hoy, Kenny and Hindes won the London 2012 team sprint gold but not without controversy. In their first attempt Hindes crashed shortly after the start and the team was allowed a rerun which resulted in their setting a winning time. It was subsequently alleged that the crash was deliberately done although Team GB officials sternly denied it.

Conclusion: the future of Olympic cycling

The UCI has indicated that it will be reviewing the London 2012 cycling programme with the Rio de Janiero 2016 Olympic Games in mind. It is thus to be anticipated that the cycling programme will be further modified for the 31st Olympiad.

In short, therefore, the roller-coaster ride of cycling at the Olympic Games seems likely to continue into the future.

Endnote

Three scheduled ‘Olympiads’ (the sixth, 12th and 13th) were cancelled (Berlin 1916, Tokyo 1940 and London 1944). However, the IOC retained their original numbering system, making London 2012 the ‘30th Olympiad’.

References

Fotheringham, W. (2010) Cyclopedia. London: Yellow Jersey Press.

Henderson, N.G. (1973) Cycling Classics, 1970–72. London: Pelham.

R. Watson & M. Gray (1978) The Penguin Book of the Bicycle. London: Penguin.

Wikipedia. Olympic Games Cycling Template <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Template:Olympic_Games_Cycling>

Posted: Tuesday 18th August 2020

This article appears in the following categories.

Upcoming Events

Whether you are looking for a gentle social meet up, or a 100-mile ride browse the community’s upcoming events and plan your next weekend outing.