Hobbs of Barbican

Posted: Thursday 28th May 2020

The new Hobbs Marque Enthusiast of the V-CC is Peter Lowry

Albert and Joe Hobbs began marketing frames in the early thirties, probably some time in 1930. The second earliest frame on the Hobbs register, which is accompanied by its original invoice, is numbered 680 and dated February 1933. Production ceased at some time during the war when the shop at 34 Barbican was bombed but started again in 1945 at the Sterling Works, Dagenham, where the two brothers had worked in munitions. The register shows that series frame numbers ended in 1953. Only small numbers of frames, built to individual order, were built after that, and advertisements for Hobbs frames ceased. To all intents the Hobbs of Barbican era ended in 1953.

The two brothers were astute businessmen. Their frames were innovative and the best models were of superlative quality. Hobbs also marketed their products skilfully, recognising the clubman as their customer base. From the early days there was a diverse product range, even the cheapest frame was identifiable with the top models.

In 1936 Hobbs introduced an extra range of top echelon models, the ‘Continentals’ (see image above). These were expensive, very well built, and desirable. They offered real performance advantages and were marketed as ‘one of the most advanced frame designs of modern times’. Finishes were opulent, with lashings of chrome, box lining and multiple bands, and using designer colours such as orange, yellow and ‘French Grey’.

Austerity ruled in the early years after the war but by 1949 people yearned for luxury products. Hobbs re-introduced their extra quality models, this time in the two model ‘Prototype’ range. By the 1950 model year the range had been extended and renamed ‘Blue Riband’, after the most successful of the prototypes, and a cycling legend was created. Paint finishes were still quite wild. It was, however, a testament to the brothers’ marketing skills that this best known Hobbs product was often of inferior quality to their earlier frames.

Production and Catalogues

In the pre-war years two concurrent but quite lavish catalogues were produced. One covered the main range of nine machines, the second covered the two model ‘Continental’ range. Although undated they are thought to be from 1937. The ‘Raceweight’ was the top model from the standard range and it survived in various forms from 1930 to the end of production in 1953.

After the war austerity ruled and customers had to wait until 1949 for a new catalogue. This was a single folded sheet and included details of the new ‘Prototype’ range, and of the reduced five model main range. The ‘Raceweight-Luxe’ continued as the most expensive of the main range but confusingly the most expensive prototype was the ‘Blue Riband’, built with a simpler lug design than the ‘Superbe’. Hobbs also produced Raceweight and Superbe tandems for road and track.

Also in the forties a series of detailed single page brochures were released covering the ‘Lytaloy’ components.

The new catalogue for 1950 included 11 models in the main range, although the numbering indicated a total of 21 machines. Rather irrelevant model names such as ‘Grasmere’

and ‘Ambleside’ were introduced for the low-end models. A second catalogue, for the top ‘Blue Riband’ range, included seven more models. The most expensive of these, the ‘Championship’ model, featured the ‘Superbe’ lug-work first introduced in 1936.

Hobbs final catalogue appeared in 1952. There was a reduced range of four in the main range, and only three ‘Blue Ribands’. The venerable ‘Race-weight’ was the top of the main line, and once again the ‘Championship’ carried over as the top frame, costing £17-19s-6d.

Innovation

The ‘Continental’ range of 1936 was technically innovative. Double tapered seat-stays and straight taper chain-stays made for a light, rigid rear triangle. There was a specially butted fork section known as the ‘TF oval fork’, said to be the ‘only really resilient racing fork’. The main frame used individually chosen butting, to ‘achieve a blend of stiffness and resilience’, referred to as ‘balanced’ tubing. All this, combined with quite upright angles, made for a subtly modern frame.

Perhaps the most striking innovation was the introduction of true fancy lug-work, in the ‘Continental Superbe’ of 1937. This made for a uniquely handsome frame, at the same time allowing the builder to ensure the even flow of brazing material throughout the lug. Hobbs were one of the first major lightweight builders to specify hand cut fancy lug-work, perhaps coincidentally with Claud Butler. This ‘Superbe’ lug-work created a benchmark for the feature which gave British lightweight frames an individuality lacking in the products of other cycle building countries for the next 25 years. The original design of the Hobbs ‘Superbe’ lugs can be traced in other builders work throughout the forties and fifties.

Below is shown a rare twin-tube Hobbs of pre-war vintage. The top tubes are twinned with the Sturmey lever mounted between, this is not obvious from the image:

Before the war Hobbs marketed some highly desirable equipment, including continental dural brake cantilevers, dural hub spindles, handlebars, cranks and stems, everything to make the clubman’s bike more exclusive.

In the forties Hobbs introduced a range of high end components under the brand name ‘Lytaloy’. These may have been manufactured elsewhere in the Sterling Works factory, thus capitalising on the considerable capacity and expertise remaining after the war effort.

There were very efficient and stylish brakes and levers, pedals, alloy cottered cranks, headset and bottom bracket, very light alloy mudguards, and even a pair of handlebars. The pedals were superb, very light, with a solid alloy centre, and the equal of Campagnolo’s pedals introduced 10 years later. With the exception of the cranks, which had their problems, these components were highly regarded by clubmen, and were to be seen on rival builder’s top end bikes.

Frame numbering

No company records have survived, but the three different systems used have been interpolated from period documents. Pre-war frames were simply numbered in series, the highest recorded number being a track iron, no 2202.

After the war the system changed, presumably to cope with larger production capacity. Numbers comprised six or seven digits, the first two representing the year of build. Thus number 4607821, a beautifully built ‘Superbe’ lugged road-path frame, was built in 1946.

In 1947 the system used until the end of production was introduced. Each four or five digit number was prefixed by a letter, referring to the month of build. The first digit indicates the year. Thus number A7151, a ‘Raceweight’ in lovely original paint and complete with original invoice, was built in January 1947. In 1950 the system simply used the prefix 0, 1, 2 or 3.

Post-war Hobbs, like most other manufacturing companies, were required to export as a pre-requirement to being allowed materials to sell on the home market. Export frames appear to have frame numbers pre-fixed with the letter X. Thus an all chrome Blue Riband road frame, which has spent most of its life in the Rockies, is numbered X3005.

Perhaps the most enduring memory most cyclists have of Hobbs is the ‘Blue Riband’ brand name. But by the 1950’s Hobbs were arguably trading on their successes of the thirties and forties. The 1950’s ‘Blue Riband’ frames were desirable, but not innovative. However, the elegant, technically advanced design of the thirties ‘Continental’ frames were. Combined with their ‘Superbe’, and in reality quite superb hand cut fancy lug-work they were Hobbs major contribution to the lightweight world. Their extensive 1940’s range of ‘Lytaloy’ branded components was also before their time in terms of design and effectiveness.Mervyn initially wrote this article for ‘Lightweight Cycle Catalogues – Vol. 1’ published by the V-CC

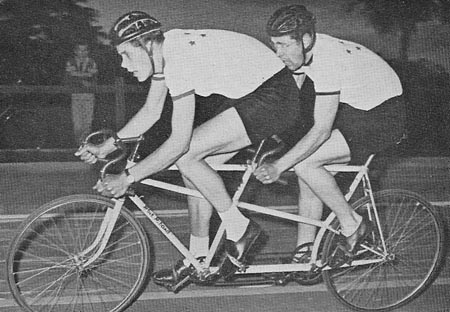

George Staples The picture below is of me racing on the E3 Southend Road in a club 25 mile event on a cycle built by myself and Dave Bedwell at the Sterling works of Jack Hobbs- Hobbs of Barbican in Dagenham. The event was on Sunday September 25th 1949, Time 1hr 7min 44seconds Rapier Road Club. Photographed by Len Thorpe. I was then only age 19.

Dave was well known at the Sterling factory and we would go there on a Saturday morning if it was possible, in those days I lived very near to the factory in Dagenham, so it was very easy just a few minutes down the road so to speak.

Dave was a dab hand at brazing, whilst I had a general knowlege of doing it as I was an instrument maker apprentice, it was Dave’s knowledge on bikes that was most important. We rode grass track, he said that if I wanted a bike it should have a short wheelbase so after he had made come calculations a decision was made to construct the bike with a 38 inch wheelbase and only ¾” rake on the front forks, this meant that the toe clips would touch the front wheel so I had to learn how to ride it and not turn the front wheel to much otherwise I would be off, so to speak. Ha said the bike should be very responsive to sprints with only a 3/4 rake and would be ideal for short distances on the road.

We only did the basic brazing to the fluted lugs and all other work was carried out during the week at the factory and I had the frame approximately two weeks later.

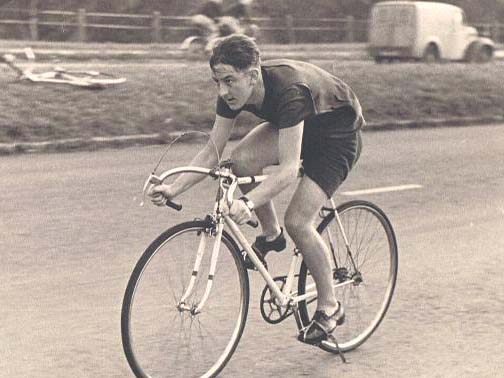

On a recent visit to the grass track racing at Mildenhall I noticed a classic Blue Riband track bike (frame number G 02631 sold July 1950) amongst the track irons collected around the Beacon Wheelers tent. I was given permission to photograph it.

I was chatting to members of the Beacon Wheelers and learned that it was being ridden by 13-year old Ellie Dickinson (see image above) and eventually she posed for us before setting off to compete. It turned out that Bob McLean of Border City Wheelers had obtained this 1950’s frame some 20 years ago in a sorry state and had it restored by Dave Yates. The machine was then used for grass-track racing by Bob’s two daughters and subsequently loaned to several members of both clubs. It was regarded highly by all who rode it, comparing favourably with modern frames that they went on to ride. Currently it is being ridden to good effect by Ellie, who you can see is very pleased with it and is churning out some impressive results.

Posted: Thursday 28th May 2020

Contents

This article appears in the following categories.

Upcoming Events

Whether you are looking for a gentle social meet up, or a 100-mile ride browse the community’s upcoming events and plan your next weekend outing.